At a personal development seminar I attended several years ago, I saw a small group of people have amazing flashes of insight into their own lives. The seminar convener was able to flip the way most people were perceiving things in their life. The most impactful conversations had to do with how people were perceiving others.

Take for example, a young man with abandonment issues named Ed. He stood up and began to tell his story.

“My father abandoned me when I was five. He left my mother with three children to take care of. He tried to contact me recently but I didn’t want to see him, especially after everything we went through because of him.”

The seminar leader said “show me abandonment.”

Ed was silent.

“The fact is your father left. Say that, say ‘my father left,’ that’s a description of a fact, not a judgment.’”

Ed’s father left and he created a story about this fact. He told himself that his father abandoned him because he didn’t love him. He told himself that this means others will eventually find him unloveable. He told himself that people he loves are going to leave him and that he shouldn’t get too close to anyone just to be safe. He continued on with this story of being abandoned by his father for his entire life. He lived and reacted to people from this perspective for the next twenty years.

As he went on to share more with us, we learned that when girlfriends didn’t call him back or didn’t pay him attention, he broke up with them. Basically in his anticipation of being abandoned, Ed had become the abandoner – which was his own worst nightmare.

Through his conversation with the seminar leader, Ed found himself on the other side of the abandonment story because he could now see that his ex-girlfriends were seeing him as an abandoner. Suddenly, the same behavior he saw in his father, didn’t look like abandonment any more. It looked more like fear. Maybe his father left because he was afraid of the enormous responsibility that came with being a parent. Maybe he was afraid of being abandoned himself, just like Ed was whenever he broke it off prematurely with women he got too close to. Maybe he was afraid of commitment.

Ed realized that he really didn’t know why his father left, or what leaving was really like from his perspective. He had always assumed that his father just didn’t love him.

Ed stood quietly for a moment, taking in the distinction between how the story he had been telling himself about his life impacted the way he lived.

“So, what you’re saying is that next time I freak out because I’m getting too close to a woman, I shouldn’t run away. I should let myself feel my pain, and hear the crazy story that goes on in my head about my worst fears, but not act as if it’s true.”

“Yes, that’s what I’m saying. And then you should share with her exactly what you’re experiencing and why. Tell her, ‘hey, sweetheart this happened when I was a kid and I am having this emotional reaction because you didn’t call back, and these are the thoughts I’ve been having, and I want to run away from you right now and never see you again, but instead I’m choosing something different.’ Try that. See what happens. Your relationship might still not work out, but it won’t be because of something that happened to you twenty years ago. This is how you change your destiny, Ed. You change how you react. You change the whole script.”

The seminar leader explained that being stuck in his own blame story about his father, Ed stayed at the “effect” side of the cause-&-effect chain of all events. Basically, most people do things in reaction to something. And most of the time, it’s in reaction to something that is not even happening any more.

“The point I’m making is that you keep living from your past. You can break this experience of reality by getting present to the fact that you are at the absolute cause of your experience not the effect. Whatever it is you’re feeling is entirely your own doing. No one else is responsible for it.”

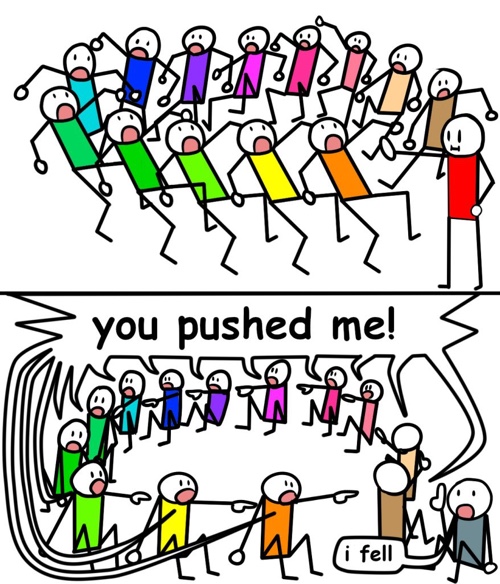

“He was just a child,” one woman objected. “And his father did abandon them. His mother had to fend for her and her children. The father leaving created this situation for them.”

“I get that,” the seminar leader said. “Really, I do. My father left us too. But what looks like abandonment to you might have been fear of commitment to the father. The father was reacting to something that happened in his own past, maybe he’d been abandoned too, we don’t know. And now Ed is living from the effect of what his father did, and now he is passing it on to every woman he gets too close to. What does Ed get from telling his abandonment story? He gets a whole lot of short-lived relationships. So what’s the point of me telling Ed that he’s right? What’s the point of me joining him in feeling sorry for himself and agreeing with him that his father abandoned him? Somebody has to break the cycle. The story is not a fact. Change the story.”

“I don’t see how this applies to me,” a woman in the room said after raising her hand to speak. “I am not causing my experience at work, it’s all my boss’s doing.”

Mary shared that her boss was creating a toxic environment by bringing in a consultant to their health care department. She described that she and her colleagues were fearful that the consultant was going to advise them to do things her boss was pushing for, and that they knew wouldn’t work.

“And this is exactly what happened,” she said. “Our boss brought in the consultant to push her own point of view on us. Everything we were afraid of became true. And now we’re angry and we don’t know what to do.”

The seminar leader asked her to separate the facts from her and her colleagues’ story about the facts. “The fact is your boss got a consultant and the consultant advised the same recommendations as your boss.”

“That’s right,” she said.

“And then you and your colleagues got together and told a story about how the consultant is colluding with your boss and undermining what you’re trying to do.”

“But that’s what happened.”

“No, it isn’t.” The seminar leader said. “What happened is that your boss brought in a consultant and the consultant gave the same point of view as your boss. Have you discussed your frustration with your boss?”

“No, we only discussed it among each other.”

“So your boss doesn’t even know that you had concerns about the consultant, or that you think her ideas won’t work. You never gave your boss the chance to hear you out. And now you’re becoming angrier and angrier, reacting to a reality you all made up together that is not even there.”

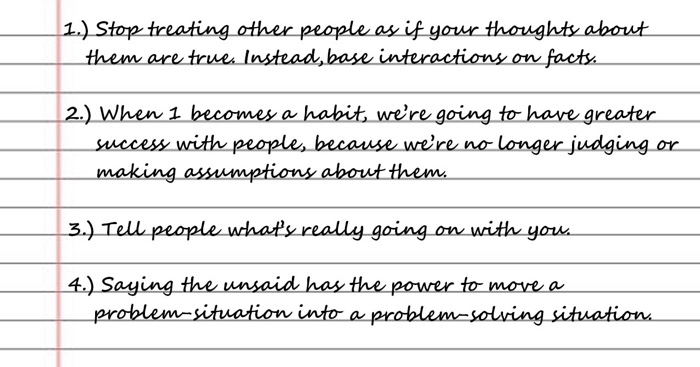

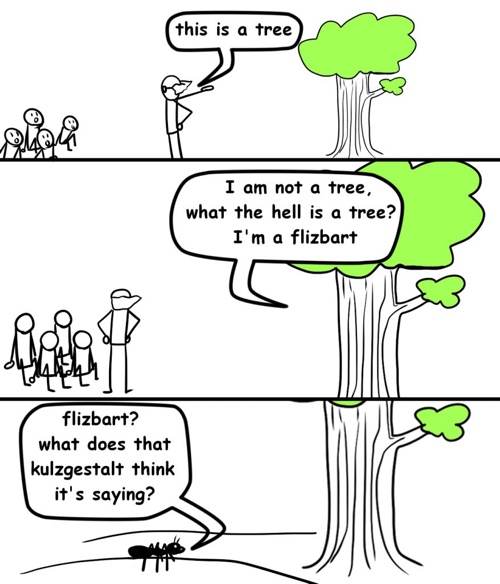

The point he repeatedly tried to get at was that we can stop treating other people as if our thoughts about them are true. Instead, we can become fully present with the people themselves and treat them according to the absolute facts, rather than our assumptions. He was able to show us where we mostly go wrong in our interpersonal lives. What he offered us was the mental discipline to always be separating the absolute facts of what happens from our judgments and stories about them. Our judgments and stories, it turns out, have to do with us and our past, rather than what’s actually going on.

He then invited Mary to do something she hadn’t thought of doing before. He asked her to say to her boss what she and her colleagues had never actually said. “There’s probably a lot of tension for everyone at work right now, but everyone is walking around with fake smiles, pretending everything is ok. I want you to break that front. I want you to walk into that office and sit your boss down and tell her everything you have been thinking and feeling. Can you do that?”

“She’s only going to get angry.” Mary said.

“You don’t know that. You can start out the conversation with ‘I’m having a problem with something, can you help me work it out?’ See what that does for you. And go in there fully recognizing that everything you and your coworkers have been telling each other about your boss has so far been just a story. Can you do that?” Mary nodded and sat back down.

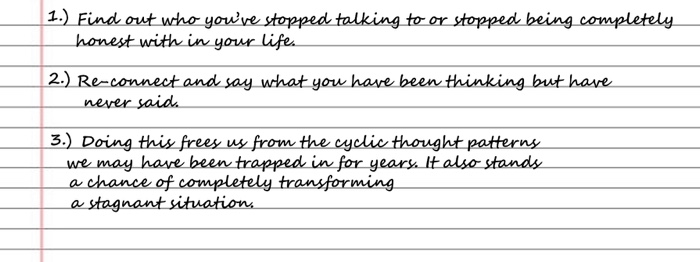

I jotted down these thoughts in my notebook:

“So one way to help identify a problem area in your life,” the seminar facilitator said, “is to ask yourself ‘where am I experiencing a loss of power, loss of freedom or loss of self-expression?’”

When we don’t effectively communicate exactly what’s going on with us we isolate ourselves from others psychologically. We are no longer truly connecting with them. By contrast when we fully share ourselves with other people, not only do they become clearer about who we are, but we invite them to do the same. This exchange deepens connection and builds trust.

“Who are you not speaking your mind to in your life?” The seminar leader asked. It might be your mother, or your friend, or you ex or even your current spouse, maybe even all of them.

He then invited us to call someone we have stopped talking to but still have a lot of things left to say to them. “And if this doesn’t apply to you, then I want you to call your best friend, your mother, I don’t care. Just call someone with whom you can share something you have been thinking but haven’t been sharing. Share yourself.”

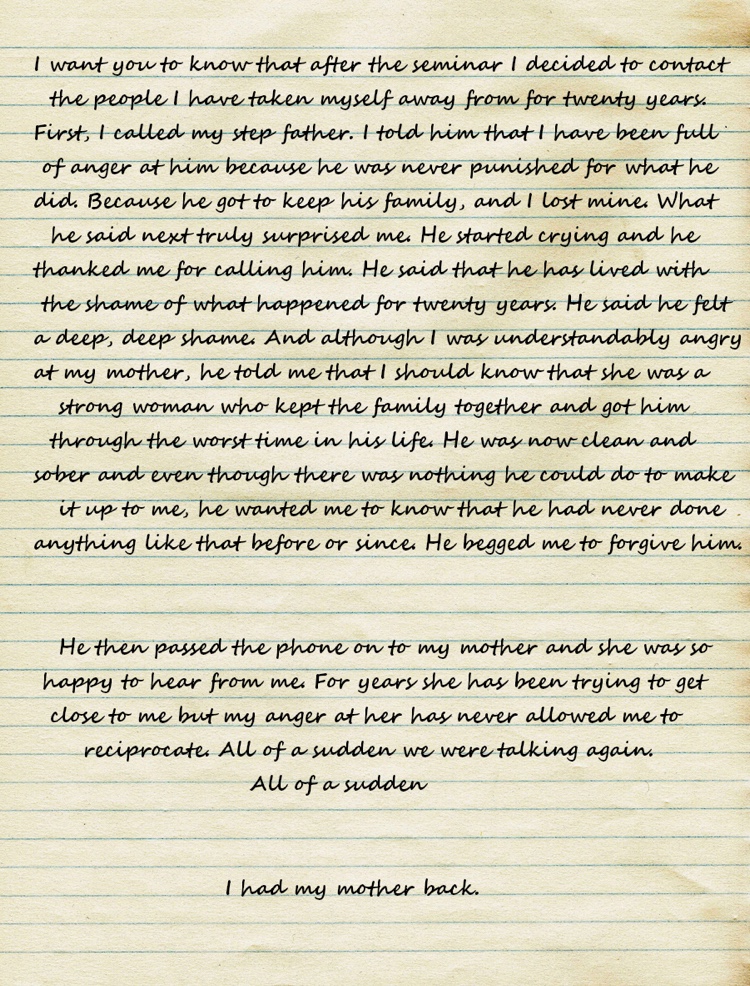

When we got back from the break, the seminar leader told us a story about a woman he worked with in England. The woman was in her thirties and had shared with the group that when she was 7 years old her step father came home drunk one night and molested her. Her mother found out about the incident and decided to stay with her husband.

When she was sixteen, 9 years after what her step father did, she moved out of the house and all but cut off contact with her family. She was upset with her step father because he was never punished for what he did. He got to keep his wife and his other children. Meanwhile, she was the one who grew up without a family. She was just as angry at her mother for failing to protect her as she was at her step father for his perversity.

After the seminar the woman felt that if she was going to affect a change in her feelings and in her life, she had to reconnect with her family, beginning with a call to her step father.

As I sat listening to the story, I felt a strong resistance to the idea that she had been pressed to contact him. She was entitled to never speak to someone who had hurt her in this way. I also felt that calling him might be seen as condoning his actions. I was sure nothing could convince me otherwise.

The young woman had sent the seminar leader a letter and he shared it with us.

I was not in favor of the young woman calling the man who sexually abused her when she was 7, even if he was drunk and it was something he didn’t do repeatedly. As a woman I was absolutely opposed to this idea. I thought it was vulgar to ask the victim of sexual abuse to reach out with an olive branch to the family that had banished her. But to my surprise, when I saw that this step had actually made her happier, had actually brought closure and healing for her, I had to reconsider my assumption.

I remembered all the spiritual teachings on forgiveness in that moment. We are taught to forgive so that we may heal. She’d been carrying this burden for twenty years, trapped in the hell of the fact that her step father behaved sexually toward her and that her mother stayed with him. And in a moment, on the insistence of a stranger, she decided to follow a different script. And the new script she chose freed her to write a different story.

I jotted down these thoughts in my notebook:

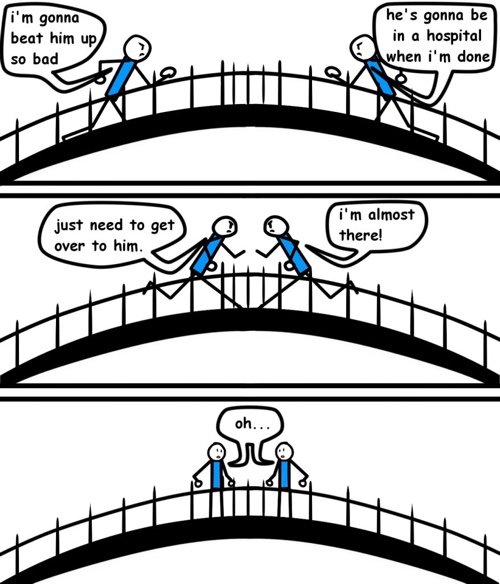

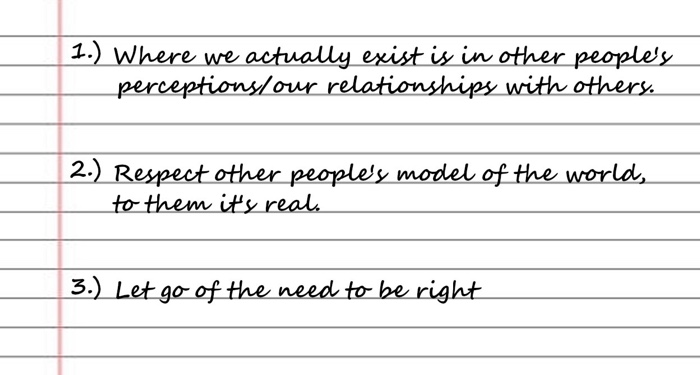

Now that we learned that we were constantly telling a story about reality that’s not reality itself, we also realized that everyone else was doing the same thing. To be truly effective in leadership, influence and communication we had to realize that we existed in other people’s stories about us – not just in our stories about ourselves. Another way of saying this is that we exist in our relationships with people.

For example, I might do something that I think is perfectly rational. It makes perfect sense to me, but to you it might look completely wrong. If I keep insisting that I’m right, we’re going to get locked into a conflict.

Instead I can choose to recognize that how I exist in your reality is real to you. And that even if we’re witnessing the same reality, what we each see can be completely different and still be true for both of us. If I can recognize that both perspectives can be right, then I can start working toward a solution without needing to be right or to make you wrong. I might disagree but I don’t discount your perspective, I respect it. I also let go of the need to be right and for you to be wrong. I create a situation where we can both be right, or even concede that you might be right and that I could be wrong.

This approach to effective communication really shined for Deepak, a man from India who had been in the United States for the last ten years. His family back home had traditional values and expectations of their eldest son, meanwhile he had developed a cultural identity as an American citizen, living in the most liberal city in the world.

“Every time I call my mother we end up in a fight. Our conflicts are not screaming matches. We just both go silent and hang up. My mother always complains about my unwillingness to marry the woman the family chose for me when I was a baby. She complains that I drink too much. I have no idea how she would know that! My father keeps telling me not to bring shame to the family, and I think he’s hinting about the pictures I sometimes post on Facebook of me and my non-Indian girlfriends. My parents want an Indian son and I’m not a good Indian son, I’m an American son.”

“No you’re not.”

“What do you mean?”

“You are an Indian son.”

“I’m not, I’m an American son. I don’t relate to those values and that culture anymore. I can’t be the son they want me to be.”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s not me.”

“But it is you. To them you are a good Indian son.”

“But I’m not.”

“But you are!”

This conversation went on back and forth for quite some time, until Deepak began to realize that not only does he exist in his perception of himself, but that he also exists in other people’s perception of him. And as far as his mother and his father were concerned, what they saw was an Indian son. Whether he liked it or not, that’s who he was from his parents’ perspective.

Deepak realized that he couldn’t change his parents’ point of view, and that he really didn’t need to. He asked himself “is it worth changing how I relate to them, so I can have a relationship with them?” The answer was a resounding yes. It didn’t matter if his parents didn’t approve of his American lifestyle, he loved them anyway, and he was happy to accommodate the way they saw him and the world. He let go of the need to be right.

I jotted down these thoughts in my notebook:

“Next time you call your parents, I want you to stop resisting. Let them be who they are and how they think. Can you do that?”

“Quite easily.” Deepak said, realizing that how he occurs to his parents is something that is within his power to influence. If instead of getting frustrated every time his mother asked him to move back to India, he laughed and offered for her to join him in the US instead, he’d be able to transform the dynamics of their relationship.

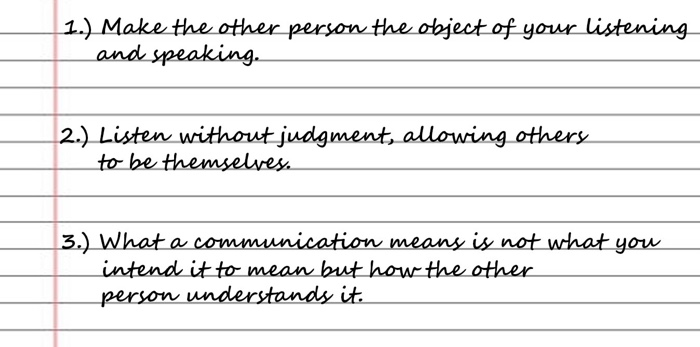

Instead of seeing listening and speaking as a self-centered activity, we can approach it as an activity that’s centered on the person on the receiving end of our communication. When we do this consistently, we begin to show up differently in people’s stories about us, because we are speaking from a place that validates their perspectives and makes them feel heard. We can finally start getting through to them and resolve conflict.

When we came back from the break, Deepak shared that he did call his mother and let her run her usual script of complaints. This time, he listened to her very intently without judging her. “For the first time I could actually see exactly that for her everything made sense. Everything she was saying was very real to her.

“I didn’t challenge her and I didn’t try to change her mind. I just let her say what she said and I didn’t feel emotionally reactive because I was focused on trying to understand her, not how she made me feel.

“When she was finished I told her that despite all our arguments in the past and all our cultural differences, we were family, and I wanted us to be close to each other again. My mother started crying and I was able to reconnect to her love for me, which was never in doubt. I don’t know what happened but I think I enrolled her in the possibility that we could meet, talk and focus on the things that are working in our relationship, instead of complaining. We can love each other despite our disagreements and conflicts. When I offered her my unconditional acceptance, she gave me hers.”

The room erupted in applause.

I jotted down these thoughts in my notebook:

In Jungian Psychology, Projection is what we call the movie we’re constantly playing in our heads. In the theory of projection, sensory information goes into our brains and then we project our interpretation of what we’re seeing/hearing/feeling out onto the screen of the external world. What we traditionally think of as the external world is just an enormous mirror reflecting us back to ourselves. We can use awareness of our projections to understand ourselves rather than the external world.

“In the realm of interpersonal relationships this means that every time Ed dated a woman who didn’t call him back or wasn’t attentive, he immediately did two things: 1) he interpreted this to mean that she wasn’t interested and 2) he broke up with her to preempt her leaving him,” the seminar leader said. “Deepak on the other hand got riled up every time his parents told him what to do. Why? What was he really reacting to? His parents can’t really tell him what to do, so why was he getting upset?”

“In the realm of interpersonal relationships this means that every time Ed dated a woman who didn’t call him back or wasn’t attentive, he immediately did two things: 1) he interpreted this to mean that she wasn’t interested and 2) he broke up with her to preempt her leaving him,” the seminar leader said. “Deepak on the other hand got riled up every time his parents told him what to do. Why? What was he really reacting to? His parents can’t really tell him what to do, so why was he getting upset?”

“You’re a grown man now Deepak, be that grown man in those conversations with your parents from now on. As for you, Ed, every time you have a strong emotional reaction to a woman not being attentive, every time you get the strong urge that you want to leave, I want you to ask yourself ‘what am I reacting to?’”

So, your mission for the next week and the rest of your life, should you choose to accept it is this: every time you have a strong emotional reaction to something, I want you to ask yourself “what am I reacting to?” And “who am I reacting to?” Chances are you’re not reacting to what’s actually happening, you’re reacting to emotional wounds from the past. Chances are you’re reacting to something that’s not even there!

Next, imagine ten different people you know. And for each person write down how you think they would react in the same situation. This will give you a range of options to respond from, rather than the automatic reaction that comes from past experience.

*The, seminar, people and events depicted in this story are fictitious. They’ve been carefully crafted by the author for educational purposes. Any resemblance to actual persons or events are purely coincidental.