I came into a world where people were killing each other.

Violence was everywhere: at home; on the playground; in the streets. Even as a child I could see that it didn’t have to be this way. At the same time, I’ve been blessed with a unique gift of storytelling. For the longest time I’ve known that my life’s purpose is to use this gift to help create a gentler, kinder world. Nobody told me “believe in yourself,” I just did.

I may be lucky in that I have always known what I wanted to do with my life, but that doesn’t mean that I’ve always been able to choose it. Especially when there’s so much pressure to conform to certain ideas of success, it’s hard for us to be authentic and true to who we are.

I am finally living the life that was meant for me. It hasn’t been easy. I hope this story inspires you to do the same.

Authenticity is a strength

In the beginning, being authentic is easy. Children behave authentically without even thinking about it. All I had to do as a kid was follow my strengths and do the things I enjoyed. I figured out what my strengths were and that I wanted to do a PhD in English when I was 12. And I kept heading in this direction for 18 years.

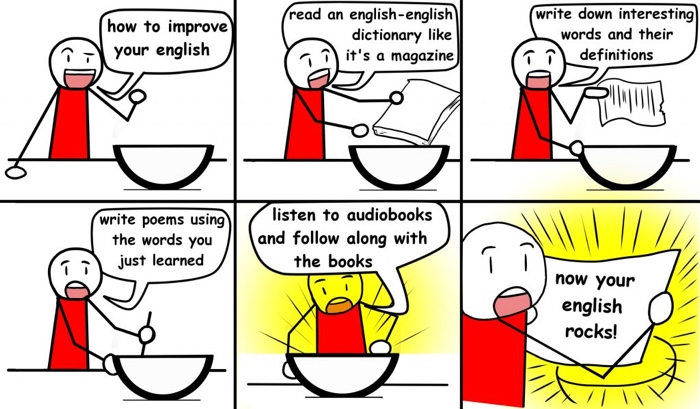

It all started when my family and I immigrated to Australia when I was 11. At that time I didn’t speak English at all. I started to read an English-English dictionary like it was a magazine. I had a notebook where I wrote down interesting words and their meaning. I wrote poems using all the new words I’d just learned. I listened to audiobooks and read along with the voice actors. Six months later I got into the top performing English class. I knew at that age that this was definitely my gift.

I then made friends with the school librarian. She taught me how to use the catalog to find answers to almost any question. I used the school library to research and write my first two novels. They were about war. I was 14.

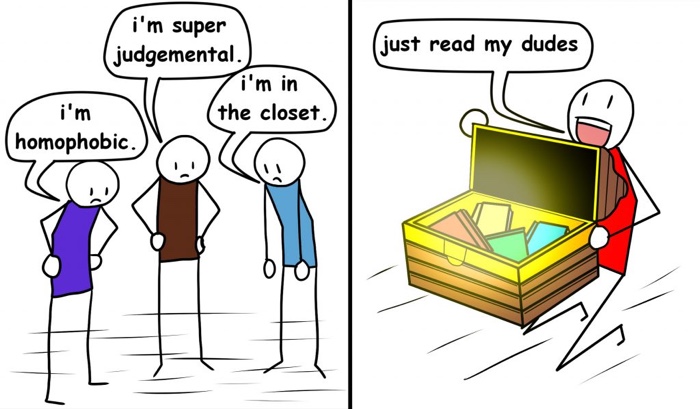

I knew books could change the world. Take To Kill A Mocking Bird, for example; Harper Lee’s one of only two novels, written and published in 1960. It sold 30 million copies and helped change the minds of an entire generation about race and the value of a human being. Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species completely rewrote the narrative on human existence for at least 150 years after it was published in 1859.

Books are powerful and new knowledge can change the world. And that’s the kind of knowledge I was after.

I kept being authentic as an adult

How do I end suffering and increase compassion? This had been the central guiding question of my life since I was a child.

So, after school I gave zero consideration to practical things like career and money. When everyone else enrolled in Engineering, Medicine and Law, I went for English Literature because I wanted to learn how to write books that changed the world. When my undergrad degree was over, I went for a PhD, just like I said I would when I was 12. At that stage I didn’t know if I’d ever get a job after graduating and I didn’t care. I just wanted to keep researching and writing, and a PhD gave me the structure and space to do just that.

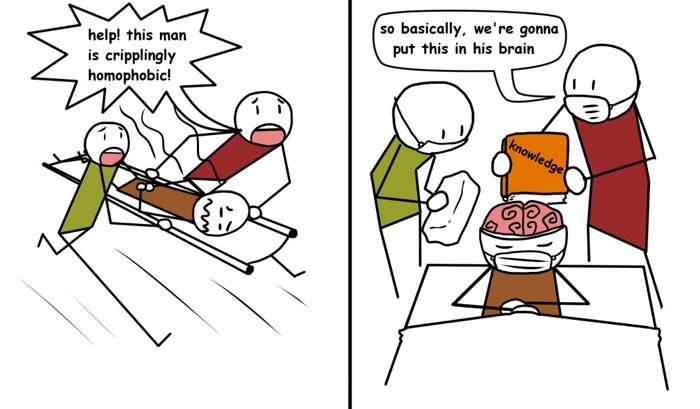

My academic research was in service of solving a major knowledge problem: homophobia caused by religious beliefs. Just like the child who wrote novels about war, here I was an adult trying to end the war on gay people in my native culture.

My first girlfriend was religious and we both suffered because of the society we lived in. So naturally I dedicated the first decade of my adulthood to solving this problem for future generations.

I ended up discovering some amazing things. I did this by fact checking every generally agreed on assumption. One common assumption, for example, was that in the Arabic culture I come from women didn’t have romantic relationships with each other unless they were copying Western countries. What a crazy assumption that turned out to be!

In truth, women where I come from have been loving each other for at least a thousand years, evidenced by some surviving poetry. No one had found this stuff before because women’s lives and their writing weren’t usually preserved or contemplated in any culture of the past, let alone mine. So it was a small miracle that I was able to find what I did.

I went into my research adventure with a Zen mind, not assuming to know anything for certain. That’s how I was able to solve these long standing knowledge problems: by noticing new things and developing arguments that were consistent with new evidence.

I also leveraged technology to my advantage. This was at a time when research was just starting to get digitalized and not many people knew how to use research databases, especially the older generation of scholars.

My research continues to help gay people who are suffering and searching for answers. When they read my work it helps them see that everything society told them about themselves – that they’re unnatural or not true to their culture – is just wrong. Slowly and over time my research also works toward changing the majority opinion in my native culture, shifting it away from deeply engrained prejudice. Just like To Kill a Mocking Bird put a dent in white people’s negative beliefs about African Americans, so too does my writing contribute to more compassion and less suffering.

When I teach my research to students who don’t know a lot about the Arab world, it helps expand their perspective. Students give feedback that my classes have helped them reach a deeper understanding of a culture they didn’t know much about before. So, in this way, my research also helps people from other cultures expand their horizons.

Knowledge really does change the world. It changes minds.

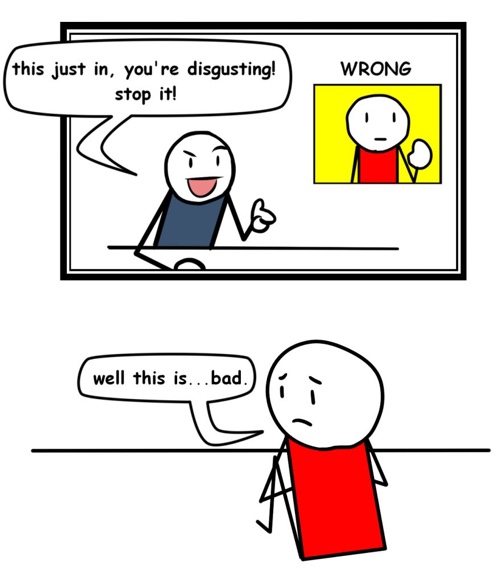

Because the books based on my research did well, I landed a job as a university professor shortly before my graduation. I was 26. I loved the profession because I still got to do what I believed in. But other aspects of the work soon started to crush my soul. Like, I didn’t want to censor myself or to pretend that a homophobic opinion was equal to a non-homophobic one. It’s like saying the opinion that the earth is flat is equal to the opinion that it is round. Corporations do that, they call it “neutrality.” They sit on the fence so as not to damage their business prospects with both flat and round earthers. They want everybody’s money. And this is how the university I was at dealt with controversy around my teaching. I on the other hand think like Desmond Tutu who said that “if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

So I left.

What does it take for someone to be real in a fake world?

And that’s when I wasn’t sure of myself anymore.

For the first time in my life I had to stop and question whether following my heart had been the right thing to do for all these years. Maybe being authentic in a fake world was hurting me. Not having social status or financial security were extremely painful for me at 30. Everyone else was buying houses and getting married. They all had 9 to 5 jobs and very clear career tracks and I didn’t. I felt tremendous pressure to have those things too.

People would ask me what are you up to these days? and I wouldn’t know what to say. I started to avoid them just so I wouldn’t have to answer that question.

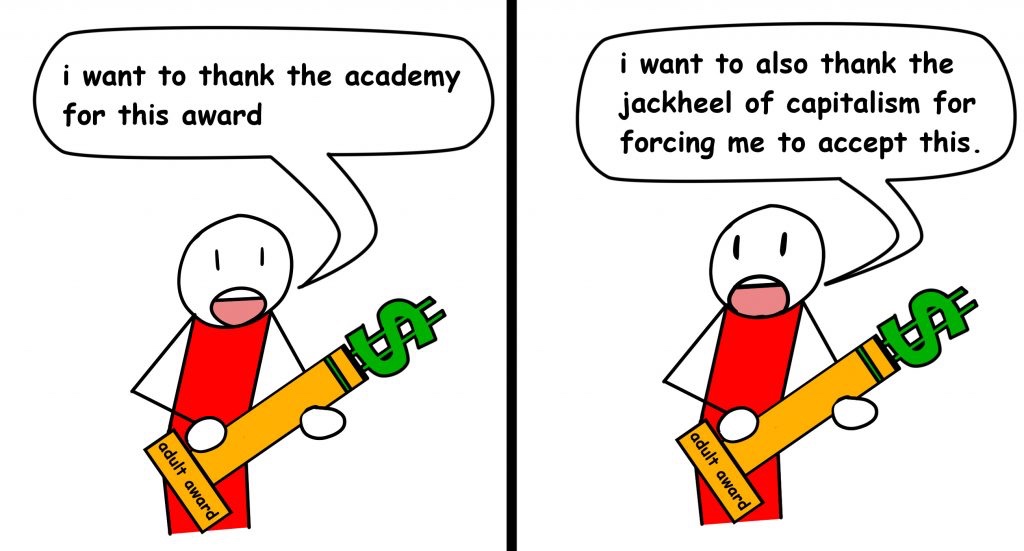

Every time I turned on the television, picked up a magazine or listened to a podcast, the message I got was clear: have money or perish. It was very Darwinian. Have money or you’re nothing. And so I felt like it was a sign of growing up that I should now focus on things that made money, instead of continuing to pursue childhood dreams of making the world a kinder, gentler place.

For the next 7 years I worked in every industry you can imagine trying to find a place so I could fit in and be like others.

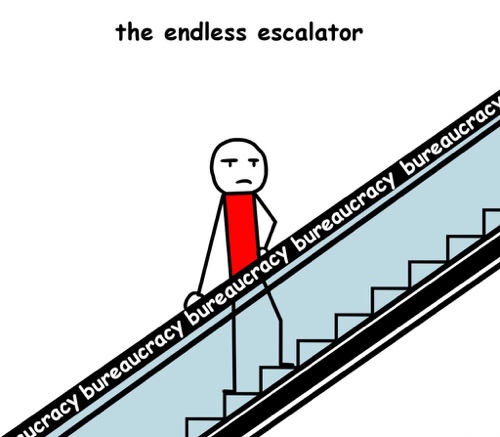

I worked at a prestigious international humanitarian aid organization but the bureaucracy was insane, and nothing got done.

At night I would go home and read books on psychology, spirituality and philosophy.

Why being authentic is important for your life

I soon discovered a theory of motivation that made a lot of sense and remembered why authenticity is important for a life well lived. The theory said that we are born with certain natural strengths and ways of thinking. It said that when we do work that is aligned with what we’re naturally good at, we feel energized, joyous and exhilarated. We can survive setbacks because we’re not motivated by results, but by the sheer love of doing what we do. This made a lot of sense to me.

I remembered those countless hours I spent, sometimes until dawn, as a teen, hunched over my brother’s DOS Shell computer writing my novels. I didn’t think anyone was going to read them, but I still wrote them anyway.

I could now see that what I intuitively did as a child was the smartest, surest way to the success that was meant for me. If it weren’t for those endless hours of practice, I couldn’t have published 6 books before I was 30, could I?

When we do work that aligns with what we love we become virtuosos, we discover our genius. We’re all geniuses at something, it’s just a matter of discovering what. Fortunately for me, I already knew what it was that I was good at. It was now just a matter of trusting this and going with it, instead of doubting it and changing course.

The theory went on to state that we can also be motivated to do things to gain approval from others or to avoid their rejection. That’s where I was at in my life. I was doing prestigious jobs that made me look good but had little impact, instead of having zero prestige and doing what may or may not change the world one day.

I was sitting in my two bedroom penthouse apartment that I lived in by myself at the time. Two bedrooms and two bathrooms with two balconies. Fully furnished. That’s what a prestigious job gives you. It makes you look good to your guests. But unless you’re doing the work that’s meant for your life, the job won’t make you happy.

I wasn’t ready to give up the appearance of success just yet. I wasn’t ready to risk the painful reality of being poor for a vision of my life that I developed as a kid. So I kept going for a few more years like this.

In the meantime, I treated my unhappiness as a research project. What gives people fulfilment? What brings joy? I asked myself.

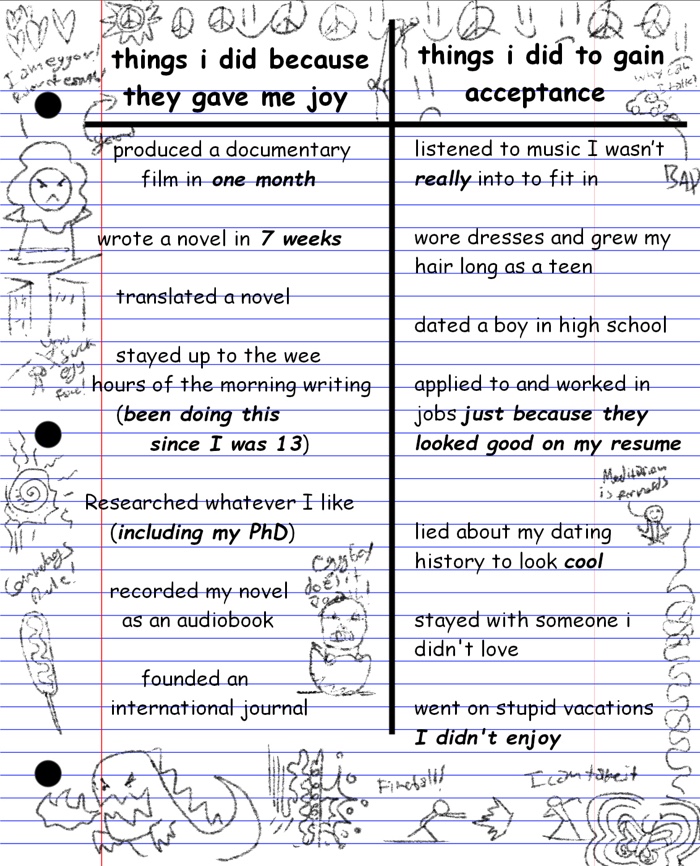

I drew two columns on a blank sheet of paper. In the first column I listed the times I did what I loved and felt joyful. In the other column I wrote a list of things I felt compelled to do because I wanted to gain acceptance.

Being inauthentic is toxic: reflecting on the wisdom of "believe in yourself" and "to thing own self be true"

Some people spend their entire lives doing things from the second column and never get to do anything from the first. They could have a ton of success and still be extremely miserable and not even know why. The trick, I’ve found, is to prioritize doing the things from the first column. Otherwise you end up living someone else’s life, not your own. And that’s how we become miserable. Being inauthentic is toxic and it’s not something we’re born with, it’s a behavior we learn as we try to avoid rejection.

Take for example when I was 5 years old. That’s when I told my parents I didn’t want to wear dresses, have long hair or play with dolls. My motivations were to wear pants I could climb trees in, and pick toys I felt excited by. I didn’t have any desire to brush or decorate anything, so I had no need for long hair either. My parents were supercool, so they let me do what I wanted and things were fine until I got to high school.

In high school the social pressure to conform hit an all time high and now I wasn’t doing things according to my preferences, I was doing them to gain approval or avoid rejection. I grew my hair long, I wore a dress for my year 10 formal (the prom in the US), and I even took an R&B-dancing boy with me. I wore make-up and punctured holes in my ears so I could wear earrings just for that night. That was seriously really gross for me. Everything I did there was to fit in. I wasn’t doing anything for myself. I wasn’t even being myself because I got the message from society, television and advertising that being myself was not ok.

I know of people who are gay and are married to a member of the opposite sex. They live a lie. And I don’t judge them for it, that’s just how intense social pressure can be.

I remember the day I gave up on trying to fit in this way. My second year in undergrad was just about to start and I still had long hair from my high school era of self-denial. I opened my eyes and I said “I’m cutting my hair today.” I went to the hairdresser in our shanty Town Plaza and I asked her to cut my hair off.

“All of it? Are you sure?” She asked, eyes bulging.

“Yes I’m sure.”

“What if you don’t like it? Are you sure you don’t want just a trim? I can blow dry…”

“All of it.” I insisted. Her hands trembled a bit but I was so happy when that hair came off. It was like the mask came off with it too.

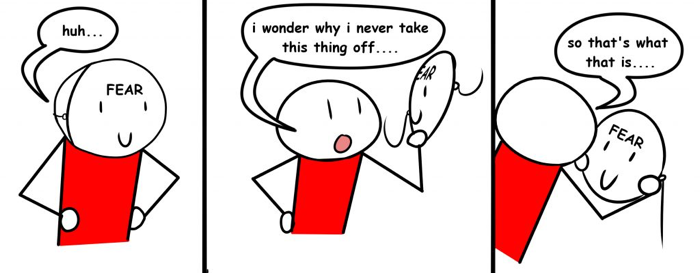

And here I was in my thirties wearing another mask and just starting to realize how I’ve been oppressing myself by basing my decisions on fear.

When we make fear-based decisions all the time, it’s because we’re running away from something. We’re only thinking about survival. And I had to think long and hard about what it was I was actually afraid of, underneath it all. And it was poverty. I didn’t care about money so much as I was afraid of being poor. So everything I was doing was to get away from rather than move toward something. So I decided to recalibrate my thinking on this point.

Being authentic as work

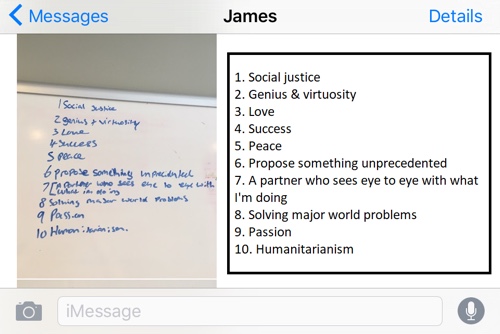

I started out by asking a friend of mine, James, who was an NLP Coach for help. He gave me some clarity on what my core values were so I can start being authentic at work.

He asked me to do an exercise with him where he got me to say the first words that came to mind that I believed were essential for my ideal career. I came up with about fifty words, but sometimes people can come up with just a few.

James patiently wrote everything down.

“Now,” he said, “we’re going to go through the list and put them all in the order of most to least important.” He went through each value I listed and asked me if it was more important than the one that came after it. If it was more important it stayed where it was, if it was less important, he moved it down the list and asked the same question about the next word.

James was extremely patient as we did this for all 50 values I originally listed. We finally had our top ten.

He took a photo of the whiteboard when we were done:

After James left I sat down staring at my top ten, reflecting on how happy I would be if I could be spending most of my time doing what I want rather than what I should. Imagine doing work that had all top ten values in it?

I didn’t have to imagine for long, that was the work I did as a kid and as a PhD candidate and even as a university professor (up to a point).

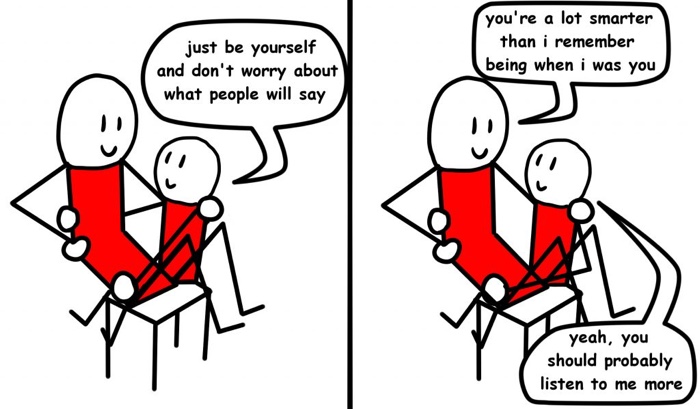

So why am I not doing what I want to do anymore? It’s essentially for the same reason I wore dresses and put on makeup in high school, isn’t it? Because I really want to fit in and want people to respect me. And so when they ask that dreaded question what do you do for a living? I’ll have a really shiny answer for them.

The older I get the more I find that I have to go back to the person I was as a child, before I began to fear the opinions of others. Isn’t it weird that the answers to my adult world problems were already known to a 5 year old?