Has A Really Good Day by Ayelet Waldman been sitting on your reading list? Pick up the key ideas in the book with this quick summary.

Lots of people struggle with their moods. Many, like Ayelet Waldman, struggle enough to seek professional help. But after years of trying – and often failing – to find solutions to her irritability, anger, frustration and depression, Waldman turned to an unexpected source: the psychedelic drug, LSD.

Placing two drops on her tongue, Waldman launched herself into an experiment to understand whether taking careful and tiny doses of the drug over just 30 days could help her toward a calmer, more accepting approach to life.

In doing so, she also began an exploration into the misunderstood substance, its history and its potential benefits. Drawing on her former legal career – in which she saw firsthand the impact of the United States’ war on drugs – she reflects on the double standards and absurdities of a nation addicted to prescription drugs but willing to incarcerate millions for possessing a substance with a great safety record.

Ultimately, Waldman was in search of the secret to having a really good day. Read this book summary, and you’ll discover whether she found it.

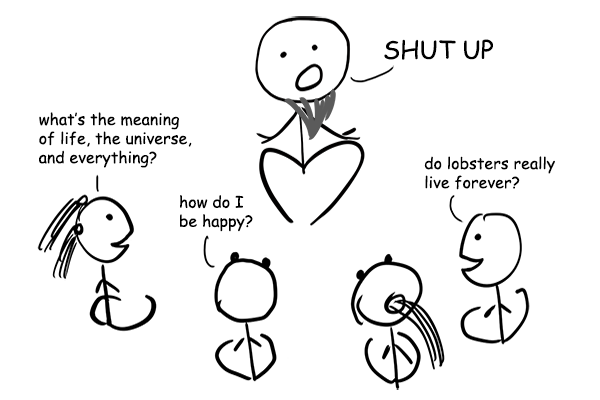

In this summary of A Really Good Day by Ayelet Waldman, you’ll discover

- how microdosing LSD works;

- why Steve Jobs and Nobel Prize Winners have attributed success to taking LSD; and

- how psychedelics like LSD can reduce anxiety and generate feelings of happiness, with fewer side effects than many prescription drugs.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #1: The author always struggled with her mood, irritability and shame, but had never found an effective treatment.

Ayelet Waldman had been at the mercy of her moods for decades. On a good day, she could be sparkling company – cheerful, friendly, affectionate and productive. But on a bad day, Waldman was worn down by self-hatred, guilt and shame. She’d start arguments with her husband, feel overwhelmed by pessimism and had little sense of self-worth, despite being a successful, published author. Her erratic moods have always made her life, and the lives of her friends and family, more difficult.

Seeking help, she turned to therapy, spending many hours sitting on the leather couches of professionals – from Freudians to cognitive behavioral experts, social workers to family therapists. She tried mindfulness – spending long periods meditating and even longer telling her therapist how much she hated meditating.

One day, crossing a bridge while driving home, she found herself considering steering to the right and hurtling into the water below. Shocked at this suicidal thought, she sought medical help. Diagnosed with a form of depression – bipolar II disorder – she started taking drugs. For years, Waldman tried numerous medications: Celexa, Prozac, Zoloft, Cymbalta, Effexor, Lamictal, Adderall, Ritalin and many more. Some helped a little, for days or even months at a time. But they had unfortunate side effects, such as weight gain, irritability and a decreased interest in sex.

Eventually, she discovered her diagnosis hadn’t even been correct. She realized her moods were fluctuating in direct correlation to her menstrual cycle, and that she had a type of premenstrual syndrome – called premenstrual dysphoric disorder – that caused mood swings at certain points in her cycle.

This discovery allowed her to learn the cycle and timing of her moods and take medication only when necessary. But when Waldman entered the perimenopause, her period became irregular, and so did her mood. Things took a turn for the worse, and she became exhausted with fury, irritation and despair.

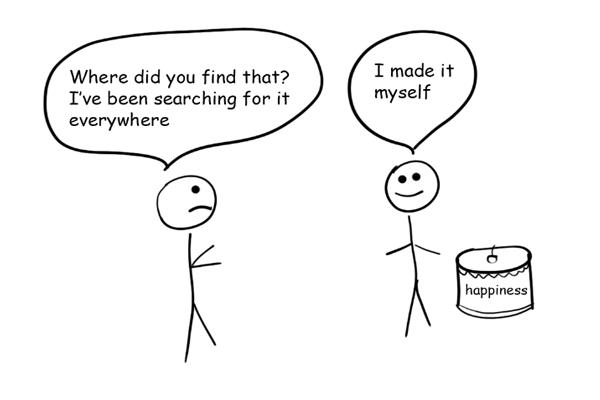

It was at this point that she happened upon the work of James Fadiman, a psychologist and former psychedelic researcher. Fadiman was popularizing the microdosing of LSD – people taking tiny doses of LSD to treat mood problems were reporting that they’d enjoyed a really good day. And a really good day was all the author had ever wanted.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #2: Microdosing is an emerging approach to improving moods, based on taking very small amounts of LSD every three days.

Microdosing is such a new concept that Waldman had to teach her computer’s spell-checker to recognize it.

The principle of microdosing is simple: The patient takes a tiny dose of LSD on repeating three-day cycles. On day one, you take your dose and monitor your mood, physical sensations, productivity and general experience of how the day went. On days two and three, you take no LSD but continue to monitor. On day four, you take your microdose and repeat the process.

The dose in question is, at most, one-tenth a “normal” dose of LSD. Your typical LSD user in search of a trip – hallucinations and an altered consciousness – might take around 100-150 micrograms. The author, like other microdosers, would take just ten micrograms at a time – two tiny drops. The theory of microdosing is that the ten micrograms should be enough to deliver an improvement in mood but without any possibility of hallucinations or other noticeable physical or mental effects.

Having learned of microdosing, Waldman was curious, but she was cautious about whether or not to proceed. She had some knowledge of drug issues and their use, having been involved in drug reform issues as a lawyer, but had never taken LSD. As a yoga-pants wearing, Instagramming, Starbucks-drinking, all-around law-abiding mother of four, the idea of becoming, in Fadiman’s words, a “self-study psychedelic researcher” felt ridiculous.

But she was suffering from her moods. Even worse, her family were suffering too. So she decided to microdose for a month. Wary of buying drugs herself, she tracked down a microdoser who was able to give her some of his supply. She tested it, to be safe, using a drug testing kit purchased on Amazon.

She took her first dose, and had a really good day.

Check it out here!

A Really Good Day Key Idea #3: The author’s first experiences of microdosing were very positive and in-line with research on LSD’s effects.

On her first day of microdosing, Waldman felt a little different, as if her senses had been heightened. She was more aware than usual of the scent of jasmine in the air and how beautiful the trees in the garden looked. She realized that she felt mindful – able to notice her thoughts and the feelings of her body. Thinking of her family prompted no annoyance, only a sense of love. She had a far more productive day than usual, and for the first time in a long while, felt happy.

On her second day, a transition day when she took no LSD, she felt a little more like her usual self again, but still had the sense that it was easier than usual to ignore her bad mood.

Day three in the cycle acts as a control day – giving her the experience of a “normal” day so as to allow better judgments about the impact of the dose. She felt her usual, irritable mood return and missed the peace and productivity of the previous two days.

As Waldman’s experiment progressed, she found significant benefits to microdosing. On day four, she realized that she had more control over her impulses and irritability. Her kids messed around over breakfast and ended up late for school, but instead of yelling, Waldman felt unusually unphased. Her dog jumped up and caused her to spill tea over a book, but as the dog sat looking sheepish, expecting a scolding, Waldman just gave it a stroke.

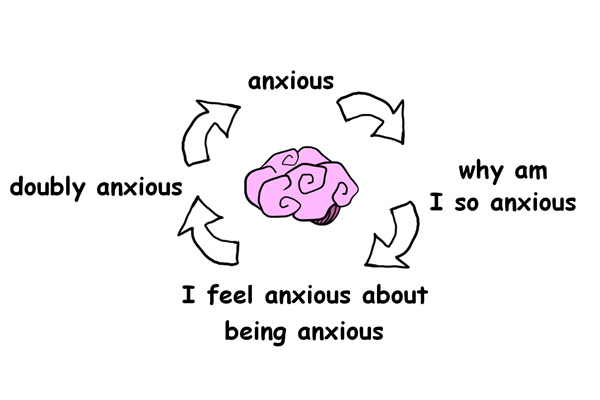

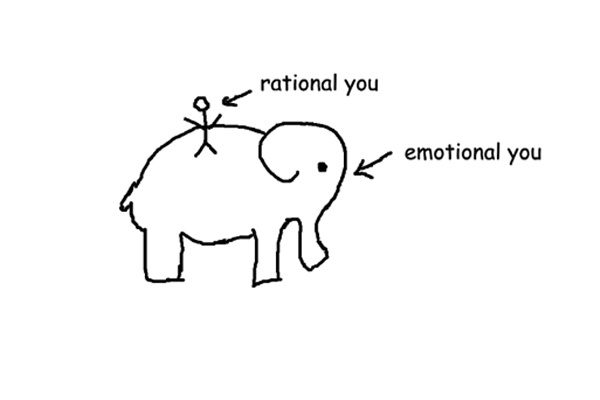

Happy at her improved mood, Waldman began looking into what LSD and other psychedelics actually do to you. They increase the interaction between serotonin, glutamate, and other factors in the brain, leading to the development of new neural connections and networks. This can help people develop new perspectives on things, such as their own problems. Researchers at UCLA and NYU have recently been able to show that psychedelic treatment can help reduce anxiety and improve the mood of patients facing death.

This seemed to fit with Waldman’s experience. After a week, she was feeling different – more capable of dealing with anxiety and irritation, more productive and, well, happier. Her early conclusion was clear: either the microdosing was working, or she was experiencing one hell of a placebo effect.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #4: Millions of people have used LSD to very little ill-effect, yet the drug is often misrepresented as harmful.

LSD was first synthesized by a Swiss research chemist named Dr. Albert Hofmann in 1938. He consumed the drug throughout his entire life and lived to be 102 years old.

Hofman’s longevity might surprise the many people who believe that LSD is a dangerous drug. The truth is, despite its bad reputation, LSD is extremely safe.

The author had heard rumors about LSD – that users experienced flashbacks for the rest of their lives, that people threw themselves off buildings thinking they could fly and that there were links between LSD use and psychotic episodes.

But there’s plenty of evidence for LSD’s safety: According to a thorough 2008 review in the respected journal CNS: Neuroscience and Therapeutics, there’ve been no documented deaths from LSD overdoses. Other studies show that taking as much as 200 times the dose Waldman was taking would cause no noticeable biological effects – although probably one hell of a trip.

Even the worst incidents of LSD overdoses are somewhat reassuring. In 1972, eight people were admitted to the hospital in San Francisco after accidentally snorting vast quantities of LSD, believing it to be cocaine. Five of the eight slipped into comas, while the others vomited continually. Within twelve hours, however, all eight had not just survived, but completely recovered.

There are, however, some signs of adverse psychological reactions to LSD use. Very small numbers of people, most of whom had existing psychiatric illnesses, have experienced psychosis or other adverse effects. But the stories Waldman had heard – about people jumping off roofs, or committing suicide? They were merely urban legends. In fact, a recent study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that lifetime psychedelic use actually correlated to a 36 percent reduction in suicide attempts.

LSD is unfairly maligned, perhaps, because in the 1960s the drug came to be linked to the youthful counterculture and associated social upheaval of the decade. Young adults protested the Vietnam war, supported the civil rights struggle, smoked pot and dropped LSD.

The drug has had a bad reputation ever since. But the overwhelming evidence is that LSD use – even at levels far higher than the microdosing Waldman was administering – is safe. Furthermore, lots of evidence suggests it has positive effects. Let’s take a look.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #5: LSD can enable better focus, creativity and problem-solving.

If you’re reading this on an iPhone, iPad or MacBook, you might just have LSD to thank. Steve Jobs, the legendary co-founder of Apple, took LSD and said that it was one of the most important things he ever did.

While microdosing, Waldman experienced far greater flow – the experience of being immersed in, and fully concentrating on, her work. And Waldman and Steve Jobs are not the only ones to credit LSD for helping with their work.

Kary Mullis was co-winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, in recognition of his work on the technique of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which enabled gene cloning, DNA sequencing and other breakthroughs. Mullis said that taking LSD was a mind-opening experience, one that was more important than any of the courses he took. He doubted whether he would have invented PCR were it not for LSD.

These anecdotes are backed up by research. One recent study – using MRI machines to follow the brain’s reaction to LSD – found that the drug generates a sort of hyper-connectivity, as ordinarily unrelated regions of the brain communicate with each other. That, it appears, enables new ideas and breakthroughs to emerge.

Earlier in his career, James Fadiman ran an experiment to explore whether psychedelics could inspire creativity. He recruited senior research scientists from innovative businesses, including a few who would go on to design silicon chips and invent the computer mouse. All of them had thorny problems they were struggling to solve. They were each given a 100-microgram dose of LSD, while Fadiman observed, guided and conducted psychometric tests.

The results were incredible: While the participants’ performance on psychometric tests improved, more compellingly, they reported experiencing sparks of intellectual intuition that solved many of their problems. Fadiman claims that a number of patents and products emerged from the session.

Not long afterward, the authorities changed their minds about letting Fadiman research psychedelics. LSD’s bad reputation had struck again. But even today, many high-powered professionals in numerous fields are using LSD. Its popularity in Silicon Valley has surged, as startup employees and tech bros try to stimulate their neural connections.

Of course, its use remains completely illegal.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #6: The US war on drugs is hugely damaging – particularly to African Americans – and it’s achieving nothing.

What’s the worst possible side-effect of microdosing LSD? The risk of getting arrested.

Although Waldman only ever had a tiny quantity of LSD in her possession, it was still enough to face a sentence of up to three years from a state court.

If you consider who the majority of prisoners guilty of drug offenses are, you’re probably thinking of a dealer caught in possession of a few weeks supply. The reality is that simple drug possession in the United States is prosecuted with great vigor, and prisons are full of people caught with modest quantities of drugs like LSD or marijuana.

Over 40 percent of drug possession arrests are for the possession of a drug that 19.8 million Americans have used in the last four weeks. Half of all federal prisoners are doing time for drug offenses, and the majority are low-level offenders.

Waldman herself was at relatively little risk of prosecution – indeed, she felt able to write about her experience. Why? Because she is white and wealthy.

America’s war on drugs has always had a racial and class element. The very first antidrug laws – created to outlaw opium in the 1870s – were focused on poor Chinese immigrants, while society ignored the large numbers of white, middle-class people addicted to laudanum. Early twentieth-century antidrug campaigns talked of supposedly drugged black people attacking white women, while warnings of the “Marijuana-Crazed Madman” from Mexico weren’t far behind.

This racism is still evident today: for every white person convicted of drug offenses, ten African Americans are incarcerated – despite the fact that white people are five times more likely to use drugs than African Americans.

The war on drugs has seen prison populations rise, and African Americans suffer racial prejudice – but for what? People are still taking drugs, many of which, like LSD, are mostly harmless. Drug production and trafficking lies beyond the reach of regulation and taxation – funding violence and crime while drugs like heroin and cocaine get cheaper and cheaper.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #7: The available evidence suggests that microdosing can be effective.

Researcher James Fadiman once believed that Sandoz Pharmaceuticals – the company that originally discovered and synthesized LSD – could’ve released a microdose version of LSD to the marketplace that could compete with the likes of Ritalin and Adderall. Unfortunately, after the drug was made illegal in the 1960s, that became an impossibility.

Nonetheless, informal research into microdosing LSD has continued, largely led by Fadiman. Already researching the use of psychedelics, he once came across a woman who told him of her experiences with microdosing. Interested, Fadiman put together a protocol based around the same three-day model that Waldman used and published it in a 2011 book. Since then, Fadiman has received around 300 requests for his protocol, and 50 reports back from people who’ve used it.

Just two of those 50 people reported negative reactions to microdosing. One person stopped the protocol halfway through the month as a result of extreme tiredness on the second and third days – the days after a dose was taken. Another simply reported that they stopped due to changes in their life circumstances. It’s possible, even likely, of course, that some of the 250 people who didn’t report back had a negative experience.

But the overwhelming picture from those reporting back to Fadiman was positive. Most people reported a mixture of emotional, intellectual, and physical benefits, as well as improvements to their personal relationships.

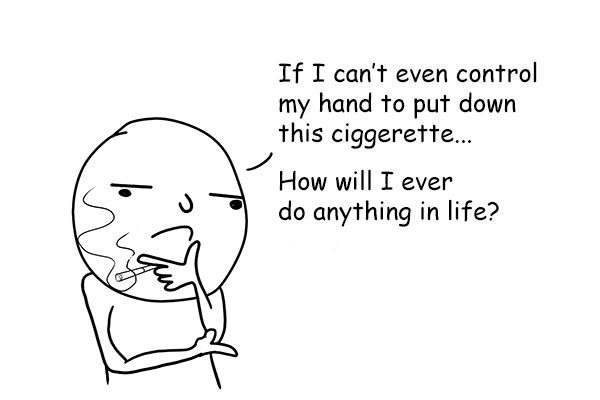

Users reported reduced anxiety, greater acceptance of life and its minor problems, greater creativity and focus and reduced conflict with their friends and families. Others commented on unusual effects: One person reported experiencing less depression in the face of their Parkinson’s disease, although the symptoms had continued. A person with a stutter saw a clear alleviation of symptoms, while a marijuana user – and in another case, a smoker – were both able to kick their habits.

Fadiman’s research is, of course, no substitute for a proper clinical study into microdosing. He hopes that someday there will be formal research conducted into microdosing’s effectiveness and safety. There are already two potential projects underway in Australia and Europe, so it’s possible that a microdosing study will become a reality in the near future.

A Really Good Day Key Idea #8: Microdosing for 30 days had a positive overall effect, although the outcome wasn’t perfect.

At the end of 30 days, and ten tiny doses of LSD, Waldman reflected on her experiences.

The only days when she had felt any abnormal sensations – mental or physical – were the days she’d taken a dose. She occasionally felt dizzy or nauseous on the day of a dose, and sometimes felt more likely to become irritable on a microdose day. On the following days, she simply felt happy, optimistic and relaxed – far better than she usually felt before her microdosing experiment.

One microdose day, Waldman had a major fight with her husband. Even then, she reported some positive signs. Normally when fighting with her husband, she ends up feeling intense shame – triggering guilt and, in turn, depression. During her microdosing month, and particularly on this occasion, Waldman felt she was more forgiving of herself after the conflict and less quick to fall into shame.

Perhaps the best indication of microdosing’s impact came from Waldman’s family: Told that she’d been experimenting with a mood medication, Waldman’s children were unsurprised, having observed clearly improved moods and behavior during the month. Her younger daughter said that even when angry Waldman had seemed much more under control. One of her sons commented that she’d merely been nicer and happier, while another said that she’d dealt with stress without yelling or shouting.

Looking back over the thirty days, Waldman came to the conclusion that she’d both felt and behaved differently. For once, she’d been able to look back at the end of the day, and think - that was a good day.

Her experiment left her positive and hopeful for the future, but also facing a paradox. She lives in a drug-obsessed nation, where ten percent of the population are taking antidepressants, and she’d finally found a drug that seemed to work. But her drug was completely illegal.

Taking a benzodiazepine – an addictive drug that can cause Alzheimer’s – would be completely fine. A doctor would happily prescribe it. But a tiny dosage of a drug with no apparent mental or physical side effects? For now, that remains a crime.

In Review: A Really Good Day Book Summary

The key message in this book summary:

Society's attitude to drugs is entirely wrong-headed. Vast numbers of people take large quantities of often addictive and potentially harmful drugs in an attempt to tackle mental health problems, with very limited success. Meanwhile, we incarcerate millions of people for taking drugs that are no more harmful, but just happen to be illegal. With LSD microdosing illegal, despite its apparent benefits and lack of harm, we potentially deny many people the possibility of experiencing more really good days.