Has Elderhood by Louise Aronson been sitting on your reading list? Pick up the key ideas in the book with this quick summary.

On a winter’s day in 2012, a group of doctors strolled the streets of Baltimore, asking pedestrians a straightforward question – “What is a geriatrician?”

Most people, regardless of age or education level, had no clue. One respondent took a particularly entertaining shot in the dark, offering “a person who scoops ice cream at Ben and Jerry’s.” America’s ignorance of geriatrics – the branch of medicine dedicated to the medical treatment of elderly people – is indicative of a larger issue. We know little about the care of older people because old age, in the States at least, is regarded with distaste, if not outright disgust.

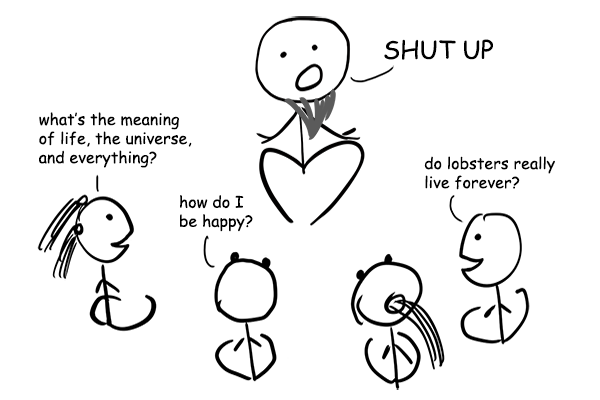

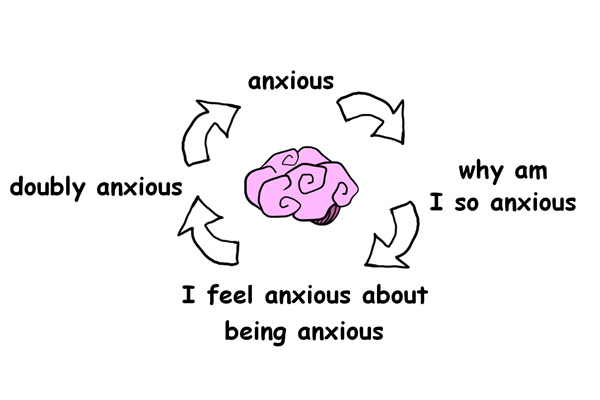

Why, in a progressive political landscape that denounces racism, sexism and most other “-isms,” is ageism still ubiquitous? Why does the medical establishment so often deprioritize the elderly? Why are cures given priority over preventative care?

Elderhood offers answers, if not solutions, to these pressing questions. We’re all headed for old age. And, barring accidents and diseases, we’ll all get there. In other words, the wisdom and lessons contained in these book summary apply to all of us, no matter where we are in life’s journey.

In this summary of Elderhood by Louise Aronson,These book summary also explain

- what happens to happiness after age 60;

- why you shouldn’t treat a side effect with a drug; and

- the recipe for a happy life.

Elderhood Key Idea #1: We’re biased against old age, and banishing our bias starts with changing our language.

When you hear the word “old,” what comes to mind? Don’t try to come up with the “right” answer. Just take note of whatever pops into your head.

Professor Guy Micco asks this question of his new medical graduate students every year at the University of California, Berkeley. If you’re like most of them, you probably listed things like “wrinkled,” “bald” or “bent over.” Maybe you also included “frail,” “feeble,” “sick” or “fragile.” These associations classify aging as a descent from the pleasures of youth to the difficulties of old age.

This bias is, in part, a matter of unfamiliarity. For the vast majority of human history, most people never reached old age. As a result, humankind has had more time to study children and adults. But now, with baby boomers hitting retirement at a rate of 10,000 people per day, older people need the attention we’ve historically directed elsewhere.

It’s also a matter of classification. We tend to think of “old age” as a period of uniformity, a blank expanse of useless years. At some point, around age 75, we’re old, and it’s all downhill from there. The US government’s Center for Disease Control (CDC) also fails to acknowledge the diversity of old age. The CDC’s recommendations for the types of care people should get at different ages vary depending on which category you fall under – child, adult or older person.

For children – that is, people under 18 – there are 17 subcategories. For adults, there are five subcategories. People over 60, however, all fall into one group. This implies that there’s no difference between a healthy 70-year-old and a debilitated 90-year-old.

Too often this results in older people not getting the care they need. According to the author, Louise Aronson, changing the way we talk about aging is the first step toward dismantling bias and embracing old age as the vibrant time it can be.

What language might be better? Well, there’s a second part to Guy Micco’s exercise. He also asks his students to react to the word “elder.” These responses are, without fail, far less pejorative, including words like “wise,” “power,” “experience” and “knowledge.”

Therefore, Aronson proposes a new word for old age – “elderhood.”

Elderhood Key Idea #2: Life after 60 can be great – the difficulty comes with being seen as old.

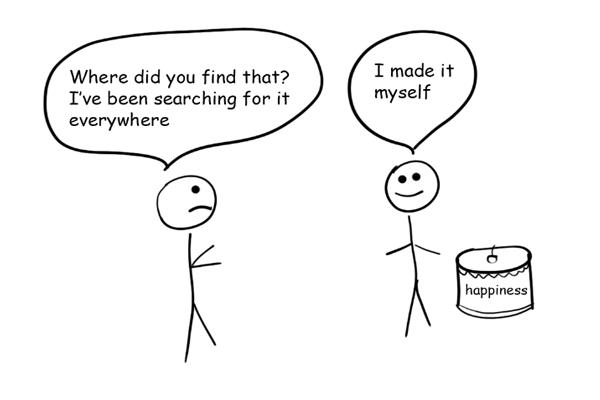

“I’m 93,” wrote beloved sportswriter and long-time New Yorker contributor Roger Angell, “and I feel great.” Contrary to popular belief, this is often the case. Aronson hears it time and again from her patients – life after 65 is great.

And the data backs this up. Studies conducted in the United States and Western Europe show that, at around age 60, people’s levels of well-being are similar to that of twenty-year-olds. After that age, those levels just increase. As Roger Angell wrote of himself and other people older than 75, “we keep surprising ourselves with happiness.”

What’s not easy is society’s reaction to older people.

Just think of all the negative terms we have for older individuals – geezer, old fart and crone. People may not always use such terms when speaking to older individuals, but they often lurk beneath the surface. Just think of the condescending tone younger people sometimes take with the elderly. “You’re not old!” or “Hello, there, young lady!” By denying the elderly person’s elderliness, such phrases imply that old age is something to be avoided.

Such instances of “ageism” – a term coined by gerontologist and author Robert Butler in the 1960s – are still widespread in the United States.

Part of this is because American culture is fixated on success and youth. Older people were once seen as closer to God. But in secular America, they’re viewed through an “industrial lens,” which favors the youthful qualities of speed and efficiency over wisdom and prudence. Even the author dyed her hair until recently because she was afraid that going grey would send the wrong signals (namely, that she was “over the hill”).

But this widespread denial of age is deeply problematic. As the fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin once put it, “To tell me my old age doesn’t exist is to tell me I don’t exist.” Old age is not a disease – it’s where we’re all headed. So we’d do well to treat those who’ve already gotten there with kindness and dignity.

Elderhood Key Idea #3: Aging people need relationships and purpose – things care institutions don’t offer.

In a popular TED talk, Harvard psychiatrist Robert Waldinger asks a profound question: “What makes us happy and healthy as we go through life?” According to the more than 80 years of data collected by the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the answer is as simple as the question is profound – relationships.

By “relationships,” we don’t mean a bunch of Facebook friends. Quantity isn’t important. What matters is quality. Anywhere between one and a few close, reliable relationships will suffice. Having a loving, stable partner doesn’t hurt, either. Second to relationships is a sense of purpose or a reason to get up in the morning.

Unfortunately, the American health-care system doesn’t take these needs into account. Nor do the people running nursing homes. Many older people living in nursing homes feel isolated, despite being surrounded by others. According to an article published in the academic journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, loneliness has been shown to increase mortality by 26 percent.

Hospital-based physicians often don’t handle the transfer of patients to nursing homes in a way that benefits the patient. In 2017, the Journal of American Geriatrics Society published an article that explored this very issue. Doctors are often pressured to discharge patients from hospitals, and there’s no system for matching patients with suitable nursing homes. The consequences of these gaps can be devastating.

Just take the example of Neeta, an elderly woman who’d fractured her hip and was admitted to the hospital for surgery. The surgery went fine, and she was discharged to a nursing home that her son had chosen because it was close to where he lived.

Nobody warned him about the facility, which gave his mother unnecessary drugs, failed to feed her sufficiently and didn’t begin her physical therapy on time. This neglect resulted in malnutrition and a massive pressure sore. Hospice became her only option.

Of course, there are happy endings in nursing homes, too. But the vast majority of elderly people would prefer to be at home. And those who can afford the luxury of in-home care do tend to be happier and healthier.

Elderhood Key Idea #4: Medications affect elderly people differently than adults.

During the first year of her medical training residency, the author made a mistake. She assumed, like many doctors and doctors-in-training, that treating an elderly patient wasn’t so different from treating an adult patient.

As a new internist, she’d inherited a group of patients from the senior residents who’d graduated. Among these patients was a woman named Anne. Anne was almost 90, and she always had a huge smile on her face. She and Aronson quickly became friends.

When Anne showed up to an appointment without her usual smile, Aronson knew something was wrong. With tears in her eyes, Anne shared the bad news. She’d been forced to put Bess, her sister, in a nursing home. Before this, Anne had been caring for Bess, but she was too weak to continue doing so.

Anne’s sadness gave Aronson pause. But after speaking to her supervisor, Aronson decided not to prescribe any medication. Anne was grieving, not depressed. When Anne came in for her next appointment, however, Aronson took action. Anne hadn’t been eating or sleeping, and her usual activities gave her no pleasure. Aronson prescribed an antidepressant.

Though Aronson had followed protocol at every turn, she’d already made her mistake. She assumed that treating Anne’s depression would be the same as treating a younger patient’s depression. It’s hard to blame her. After all, before the National Institute of Health’s 2019 Inclusion Across Lifespan Policy, medical drug trials were not required to include older people. Ironically, most people who require these drugs are usually elderly.

For example, most cases of atrial fibrillation occur among older people, but the drugs to treat it often have an unfortunate side effect: they cause patients to become confused. But since the drugs are “trial proven,” they continue to be prescribed, though they’re potentially unsafe.

As it turned out, the antidepressant that Aronson had prescribed could cause elderly patients to develop extremely low sodium levels. Low sodium has many effects, including lethargy and confusion. In severe cases, it can cause death. Aronson only learned of the antidepressant’s impact on older people after unearthing some recently published case reports.

But, by then, Anne had already been readmitted to the hospital, requiring urgent care. Her son, Jack, had already questioned Aronson’s competence. It was an experience as humbling as it was educational.

Elderhood Key Idea #5: Old age is regarded as a sort of disease with inevitable symptoms.

A 95-year-old once went to see his doctor about knee pain. After a cursory look at the knee, the doctor asked what the man expected. His knee, after all, was almost 100 years old. “Yes,” the man responded, “but so is the other one, and it doesn’t bother me a bit.”

This anecdote points to an unsettling fact. More often than not, people, doctors included, regard age itself as a kind of disease. A knee that’s healthy at 95 is considered an aberration, a surprising exception to the rule. But equating elderhood with certain symptoms can have devastating consequences.

Take the example of Lynn, a 79-year-old woman who lived with her daughter, Veronica. Lynn was healthy and happy, but one Friday night, she started acting slightly strange. She seemed slower than usual, and on Saturday morning, she was oddly apathetic. She and Veronica had planned to attend a special event that day, but she was suddenly uninterested.

On Saturday night, the oddness continued. While preparing for bed, she failed to put on her pajama bottoms. In the middle of the night, Veronica found her standing before the bathroom mirror, seemingly disoriented.

Unsettled, Veronica called 911. When the paramedics arrived, they asked whether Lynn had adjusted her medications recently. When Veronica responded negatively, they heaved the equivalent of a professional sigh. She’s nearly 80, they said, and it’s the middle of the night. Bewilderment is par for the course.

They were sorely mistaken. Though many elderly people do suffer from some form of dementia, being old doesn’t always imply being senile. Old age does not necessarily go hand-in-hand with midnight confusion and general apathy.

In fact, Lynn had begun to bleed inside her skull on Friday night. On Sunday morning, after the paramedics left, she suffered a major stroke.

What makes this story particularly worrisome is that the paramedics were probably following protocol. They almost certainly had Lynn’s best interests at heart. But they, like most people in the world of medicine, held assumptions about what it means to be old.

In the end, after months in the hospital, Lynn returned home. But she was forever changed by her stroke.

Elderhood Key Idea #6: Prescribing drugs for every symptom can result in drug-induced health complications, especially among the elderly.

Aronson once had a patient named Dimitri. At age 79, with advanced Parkinson’s and a slew of chronic diseases, including dementia, Dimitri took ten medications, many of them multiple times daily. That might seem normal for someone Dimitri’s age, but, far too often, patients take drugs to treat side effects caused by other drugs. This can have disturbing consequences.

When Aronson first met Dimitri, he was almost unresponsive. Lying in bed with his eyes closed, he could hardly reply to Aronson’s questions. What was his name? He silently moved his lips. Was he in pain? No response.

However, Dimitri seemed quite fit. He was muscular, with healthy organs. Aronson, trying to figure out what was going on, took a closer look at his list of medications. None was uncommon, and all were appropriate to his diagnoses. However, two of them were included on a list of medications that might have adverse effects on older people.

Upon seeing this, Aronson called Dimitri’s daughter, Svetlana, and asked how long her father had been in such a dire condition. To Aronson’s surprise and horror, Svetlana responded that Dimitri was completely healthy a year ago. Even six months ago, he’d been able to walk, talk and read.

Aronson immediately stopped eight of his medications and began reducing the others. Within a week, Dimitri was sitting up. Day by day, he began talking more, as well as eating and moving. Six weeks later he moved to the assisted living unit, where he took up painting and became romantically involved with a fellow resident.

So, what had happened? Well, Dimitri had been the victim of a “prescribing cascade.” This refers to when a prescribed drug’s side effects are treated by another drug. The side effects of the new drug are then treated with a new drug. This continues until the patient is taking a great deal of medication.

First, Dimitri was prescribed medication for his blood pressure. When that caused him to develop gout, he was prescribed yet another medication, and when that caused heartburn, yet another. This continued until he’d developed drug-induced Parkinson’s and dementia.

Of course, prescription drugs are not the primary cause of Parkinson’s and dementia. But we’ll never be sure how many cases like Dimitri’s go undiagnosed until we cease to prescribe drugs for problems caused by other drugs.

Elderhood Key Idea #7: Many of the resources that aging people need aren’t paid for by insurance.

For most older people, the ability to function is more important than life itself. In a recent study of elderly patients with serious illness, the “inability to get out of bed” and “needing around-the-clock care” were listed as worse than death.

But in the United States, many of the resources that would help aging individuals remain independent – such as walkers, hearing aids, dentures and glasses – are considered “nonmedical.” Therefore, health-insurance providers don’t cover them.

If you’re rich, you can afford these things. Those on Medicaid – the US government’s health-care insurance program for low-income Americans – may also have access to them. But most people are neither very rich nor very poor. Nonetheless, they’re forced to foot the often sizable bill.

By defining treatments as “medical” and assistive devices – hearing aids, glasses and so on – as “nonmedical,” the United States puts patients in a confusing position. For instance, it’s possible to get laser eye surgery, but not the far simpler solution – glasses. Likewise, you can get a cochlear implant when what you actually need is a hearing aid. How did this happen?

Well, it’s political. American health care classifies high-priced, surgical interventions as “medical” because they benefit the industries that produce pharmaceuticals and medical devices. These industries, in turn, support political candidates who agree to uphold this taxonomy. Knowing that this support will get them reelected, these politicians don’t fight for a reclassification of assistive devices – hearing aids, glasses and so on – as “medical.”

As things stand today, old age is defined by just such injustices. In the United States, the current medical system is designed to cure diseases, not provide care that might prevent their development. Meanwhile, Western society defines “looking good” as “looking young.” If we don’t challenge these prejudices, both personal and political, we can’t be surprised if they negatively impact our own elderhood.

Final summary

The key message in these book summary:

We’re all headed toward old age. Improving our own elderhood means challenging the societal prejudices and misconceptions that relegate the elderly to the sidelines of American life. That not only means changing how we talk about the elderly but educating ourselves about their varied and unique medical needs. If we can do this, we’ll be well on our way toward enjoying an elderhood characterized by joy and fulfillment.

Actionable advice:

Talk about death.

Though it’s difficult to do, studies show that if doctors avoid speaking about death, people tend to be more surprised and upset when a loved one dies. Furthermore, speaking openly about death acknowledges a difficult truth – we’re all going to die. There’s a bright side to the bleakness, however. By acknowledging death, we give ourselves the power and opportunity to say things that might otherwise be held in until it’s too late.