Has Factfulness by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling, Anna Rosling Rönnlund been sitting on your reading list? Pick up the key ideas in the book with this quick summary.

In a perfect world, journalists would always present the news in a completely accurate way, and they’d give plenty of relevant context to make it even more impactful. But, unfortunately, we live in the real world, where journalists are in the business of attracting readers, and readers love things to be both super simple and full of drama. As a result, our worldview has become skewed — a poor representation of what the world is really like.

At the heart of our messed up worldview is the belief that people around the planet are worse off than they were before. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, there’s far less poverty than ever before, people everywhere are living longer and less of the world is being run by sexist and oppressive patriarchies.

All this positive change is the result of a global economy that continues to lift people out of poverty and increase their income levels. Indeed, if we combine middle- and high-income countries, we account for 91 percent of humanity. That’s pretty amazing, considering that, just 200 years ago, 85 percent of the world was mired in poverty.

These book summary help us understand just how much progress has been made, and how we all can learn to overcome the negatives to see our world in a positive, accurate light.

In this summary of Factfulness by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling, Anna Rosling Rönnlund, you’ll discover

- why we shouldn’t think of things in the black-and-white terms of East and West anymore;

- why blaming pharmaceutical CEOs is probably shortsighted; and

- why natural disasters are less deadly than they used to be.

Factfulness Key Idea #1: “Megamisconceptions,” like the East-vs-West divide, prevent us from seeing the world accurately.

Here’s a question for you: Over the past 20 years, what has happened to the level of extreme poverty in the world? Has it nearly doubled? Stayed the same? Or been nearly cut in half? If you guessed that it has been nearly halved, you’re one of the few people to answer the question correctly.

In the United States, only five percent of people got it right; in the United Kingdom, only nine percent picked the right answer – and those who got it wrong include some of the brightest experts working today. The reason why so few people have an accurate understanding of the world is due in large part to our natural instincts and what the author calls megamisconceptions.

Some misconceptions are mega because of how deeply they mess up our understanding of the world. One of the big ones is Westerners’ “us-versus-them” mentality – that is, the idea that West and the East are fundamentally different and somehow at odds with each other. This is also referred to as the outdated concept of the “developed world” versus the “developing world.”

When the author gave lectures, he noticed that many students still thought that the East was filled with countries where birth rates are out of control and where religion and culture prevent the creation of a modern or “Western” society. As one of Rosling’s students put it, “They can never live like us.”

But who exactly is “they,” or the “East,” or the “developing world” – is both Japan and Mexico City still part of the East? Are China and India still considered incapable of being home to modern cities?

Back in 1965, if we just looked at the child mortality rate around the world, which is a great test of a nation’s overall health, education and economic systems, 125 countries would fall into the “developing” category of having over five percent of their children die before their fifth birthday. Today, that category only contains 13 countries.

In other words, there is no “West and the rest” anymore.

Factfulness Key Idea #2: Other megamisconceptions come as a result of our negativity instinct.

Here’s another question: In all of the world’s low-income nations, how many girls finish public school? Twenty percent, 40 percent or 60 percent? Are you already starting to guess that the answer will likely be the more positive one?

Indeed, 60 percent of the girls in low-income nations finish public school. What’s more, on average, all 30-year-old women have spent nine years in school. That’s only one year less than the worldwide average for 30-year-old men.

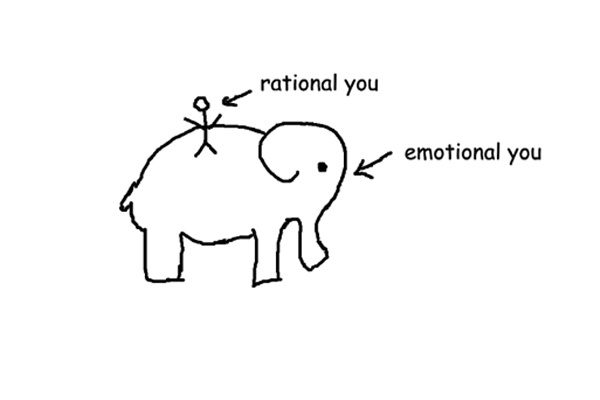

These are just a couple signs of the amazing progress that’s been made – progress of which very few people are even aware. So why do these positives get overlooked? Well, one reason is our negativity instinct, which leads to the second megamisconception: that the world is getting worse.

The truth is, across the board, in just about every single measurable statistic, from life expectancy to (lack of) poverty, the world has gotten better. Yet, as human beings, we tend to focus on the bad.

In 1800, 85 percent of the world lived in extreme poverty; today, that percentage is down to nine! This is completely amazing, and yet you’re not going to hear about it in the news. News outlets are far more likely to report on natural disasters, crimes or any of the other dismal deviations from the otherwise excellent trajectory of the world.

Back in the 1980s, there was far less news to consume and entire ecosystems could be demolished without so much as one story in your local paper. Now, the entire world’s newspapers are at your fingertips, exposing you – and almost everyone else on earth – to more bad news than ever before. This overexposure gives the impression that things have gotten far worse in the past twenty years.

But remember, for every death you read about due to a flood or earthquake, there are many who survived the disaster that aren’t being reported on. In fact, thanks to advancements in affordable building materials, low-income communities are far safer than they’ve ever been. Today, the rate of deaths due to natural disaster is only 25 percent of what it was 100 years ago.

Factfulness Key Idea #3: Our fear and size instincts, as well as our straight-line instinct, also contribute to our skewed understanding of the world.

If you see a chart with a line that’s going steadily up, your brain will likely tell you that this straight line will continue going up for the foreseeable future. However, very few charts have straight lines. Think of your own childhood growth rate; for a while, your height could probably be measured in a straight line, but then you hit a peak height, and it leveled off.

We think the same about population: our third megamisconception is that the world’s population will continue going up, up, up, when the fact is that we’re close to hitting our peak.

According to the UN forecasters, whose job it is to study population growth, the world population will flatten out between 2060 and 2100. There are a few reasons for this, but a primary one is that, as poverty decreases, people tend to have fewer children.

Hundreds of years ago, the average mother gave birth to around six children due to the high mortality rate and the need to have kids who could help with the farming or factory work. This is no longer the case; now, thanks to education, birth control and less poverty, the average mother has 2.5 kids. By 2060, the children already born will have grown up and had their kids, at which point the population is predicted to level off at around 11 billion or so.

So really we shouldn’t be worried about never-ending population growth/overpopulation. Yet, we do worry. This is because of our fear and size instincts.

The reason for our fear instinct is rather self-explanatory – being afraid can keep you safe from threats. Our ancestors developed this instinct in more dangerous times when humans were at risk from saber-toothed tigers and rival tribes. As there are no longer as many immediate threats, we now tend to misplace our fear, worrying about threats that don’t really exist.

And our size instinct leads us to overestimate the dangers that our fear instinct creates for us. Take our fear of violence. We are exposed to a greater number of news reports on violence than ever before, so we think there is more of it. But the real numbers show that crime is down. In the United States, 14.5 million crimes were reported in 1990. In 2016, that number was down to 9.5 million.

Factfulness Key Idea #4: People tend to over-generalize and mistakenly think certain outcomes are unavoidable.

One of the best ways to combat many of our worst instincts is to collect the right data and give it the appropriate context. If you read that 4 million babies died last year, the size of that number could lead you to believe that we live in terrible times. However, if you look up how many babies died in 1950, and see that the number is 14.4 million, you get a much more accurate understanding of the times we live in.

Yes, in an ideal world, no babies would die – but, in ours, it’s important to contextualize misfortune in order to perceive progress. To have reduced the number of yearly infant deaths by ten million in less than 70 years is a great accomplishment, and we need to recognize such progress.

Furthermore, we need to avoid making unhelpful generalizations.

Some generalizations are accurate – the cuisine in Japan is different than the cuisine in England – but many others, especially those about race and gender, are like roadblocks to an accurate worldview.

Here’s another question: How many one-year-old children in the world have been vaccinated against some disease? Twenty percent, 50 percent or 80 percent? Yes, that’s right, 80 percent – nearly all of the world’s kids have some form of basic health care.

Not only is this statistic mind-blowing when you consider that many people would have thought it impossible just a couple generations ago. It also defies a common generalization that certain countries – perhaps in Africa or the Middle East – will never have the right infrastructure to get these kinds of medicines to children, and are destined to be forever mired in poverty.

Rather than thinking in terms of tribes, religions or cultures, a more accurate worldview would be to see the world in terms of income levels. This works well because, no matter its religion or culture, a country that’s escaped the bottom income level will soon see improvements in things like education, health care and basic infrastructure.

Factfulness Key Idea #5: To see the world accurately, people need to take in multiple perspectives and avoid casting blame on individuals or groups.

One of the best ways to avoid overgeneralization is to travel and see other cultures firsthand. This is also a great way to gain multiple perspectives, which is hugely important, since taking in limited perspectives is another big roadblock to an accurate worldview.

If you were to go to Afghanistan today, which is one of the few countries still working to escape extreme poverty and the bottom income level, you’d meet young people who are nonetheless preparing for a modern life.

Likewise, if you were traveling in the 1970s and visited South Korea, you would have seen a nation rapidly transforming from a bottom-rung to a middle-income nation under a military dictatorship, a fact that challenges the limited worldview that only a completely democratic government can lead to a healthy economy.

In fact, of the ten fastest growing economies in 2016, nine of the countries are not very democratic. So don’t think that only democracy can lead to economic growth; the reality of the current global economy proves otherwise.

The fact of the matter is that the world is very complicated, which is why it’s smart to get as many perspectives as possible. It’s also why it’s very shortsighted to single out one individual or even one group as the source of a problem, as we commonly do.

For example, pharmaceutical companies often don’t research solutions to malaria, sleeping sickness and other diseases that only affect the poorest populations. The reflexive response might be to blame the CEO of the pharmaceutical company, but isn’t the CEO just following the lead of the board members? And aren’t the board members just doing what the shareholders want?

Or take the recent refugee crisis. When Europeans saw photos of dead bodies washing up on shore after their poorly made boats fell apart, many people instantly cast blame on the traffickers.

But if you keep digging to the core problem, you’ll see that the reason refugees are on the shabby boats in the first place is because European law requires a refugee traveling without a visa to be approved as a valid refugee by the staff of the boat, plane, bus or train they’re trying to board. But this is so difficult that it never happens. Also, European law allows authorities to confiscate the boats used for refugee transportation, so no trafficker is willing to use a good, reliable boat.

Factfulness Key Idea #6: Avoid making rash decisions and exaggerations, and stick to the facts in education, business and journalism.

The final troublesome instinct we have is the urgency instinct, which leads us to make rash decisions that often end up being misguided or just plain bad.

Our most important problems, such as pharmaceutical companies not researching certain diseases or refugees fleeing in shoddy boats, are usually complex and require careful consideration of all possible repercussions. And this means that a problem hardly ever has a clear-cut solution.

It’s of the utmost importance that we consider every possible outcome before making important decisions. This means sticking to a worldview based on facts, even if people with good intentions think exaggerations will help.

There’s no doubt that climate change is an important matter, but some are eager to spread the message of the worst-case scenario while ignoring the best- or likeliest-case scenarios. In their opinion, we need to spread fear in order to get people to take action. But, in the long run, exaggeration can make people feel deceived, which could lead to the climate-change activists losing credibility, which should be of utmost value.

Facts and accuracy should be honored in all areas of life, including education, business and journalism. Teachers should always be sure they’re using up-to-date information. So much of our continued “West and the rest” thinking stems from old information and outdated perspectives.

Businesses and investors can use an accurate worldview to their advantage, too. All signs are pointing to Africa being a burgeoning land of future business and now is the perfect time to invest. You’ll not only be helping an area grow; you’ll also be ahead of the curve.

Journalists are like everyone else, burdened with the same misconceptions and instincts, and while we can hope they’ll be as truthful as possible when reporting on the world, readers should not rely on one source for all their information. Remember, taking in multiple perspectives is key to true understanding.

Final summary

The key message in these book summary:

Factfulness is in short supply these days thanks to some basic yet major misconceptions and the fact that our very human instincts can sometimes work against our own interests. While a great many people are living under the belief that the world has gotten worse, the fact is that it’s gotten a whole lot better in an incredibly short amount of time. In just about every single measurable category, life is better now than it was 200, 100 or even 50 years ago. People are living longer, there’s more access to health care and education and there’s far less poverty. Recognizing this takes looking beyond your one news channel and accessing the real facts and putting them into context.

Actionable advice:

Teach your children well.

If you want your children to grow up to respect factfulness, teach them what the past was really like, including the bad parts. They should also be taught how to recognize useless stereotypes and how to hold two seemingly competing views at once, such as, there is pain and suffering in the world, but things are getting better for a lot of people. Also, teach them how to consume news by showing them how to recognize when the news is being overdramatic and encouraging them not to feel too anxious or hopeless.