Has Mandela’s Way by Richard Stengel been sitting on your reading list? Pick up the key ideas in the book with this quick summary.

Many of us have wondered how Nelson Mandela continued to show high levels of love and compassion throughout his life, despite the many setbacks he faced. Faced with years of living in hiding, with prison and defamation, perhaps most of us would become bitter and filled with hatred. But not Mandela. How did he do this?

This book will show you the leadership and people skills of the first black president of South Africa. It will provide you with the key principles from Nelson Mandela’s life, showing how he became the man he was.

Among other things you will discover how Mandela treated the man who wanted to execute him, why he washes another prisoner’s chamber pot, why he insisted on wearing a three-piece suit and why he learned the rules to rugby.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #1: Courage is not fearlessness. Courage is learning to cope with fear.

At certain times, we all wish we had been born “naturally” courageous. But none of us is born without fear. The same was true for Nelson Mandela; he learned at an early age that he was not born fearless – fear was something he would have to learn to deal with.

Dealing with our fears – being courageous – is a choice and it was at age 16 that Mandela first made this choice.

He was 16 when he participated in a traditional Xhosa initiation ceremony – lining up with other boys to be circumcised by a frightening man wielding a large blade. Each boy bravely shouted, “I am a man,” immediately after being “chopped,” but when it was Mandela’s turn, the agony forced him to hesitate for some moments before he could shout out those symbolic words.

This humiliating experience convinced him that he was not born with courage, but he pledged to himself that he would never again falter – he would learn to conquer his fears.

Conquering fear means looking strong, even when you are afraid. Pretending to be brave is bravery. Mandela showed this time and time again. He became a great leader simply by always appearing courageous.

A great example of this was a flight in a small plane across South Africa when an engine failure forced an emergency landing. The bodyguard who’d accompanied him during the flight afterwards described with amazement how calm Mandela had been while their lives were endangered. He simply read the newspaper. Mandela himself, however, later confessed in private that he’d been truly terrified but refused to show it!

Because courage is a choice, everyone can be courageous. It doesn’t mean risking your life. It means learning to cope with your anxieties and fears every day. Mandela’s ability to hide his fear was calming and comforting to many of his companions and followers; it is an inspiring leadership trait that we can all develop.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #2: When faced with difficult circumstances, learn to think and act in a calm, measured way.

It is admirable to be in control of yourself in tense situations. And one of the main expectations of leaders is that they always remain calm and act appropriately.

Such measured behavior may not be our natural temperament, but it is something we can develop through exercising self-discipline – a skill that Mandela knew he needed to be a successful leader.

As a young man he was hot-headed and volatile; his reactions to situations were not always calm. But 27 years in prison helped him to master the art of measured responses to tricky situations.

This self-control proved vital in dissipating a tense situation in 1993. The anti-apartheid African National Congress party’s militant young leader, Chris Hani, had been murdered. South Africa was at a knife edge and could have descended into civil war. In this tense situation, Mandela did not panic. With calmness and self-control, he addressed the nation and inspired the people to display self-discipline in the way they reacted.

This measured response to the potential crisis was instrumental in averting bloodshed and disorder.

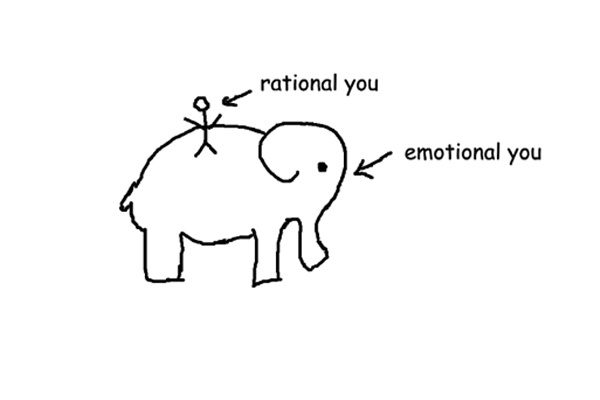

But being so self-controlled and avoiding passionate flare-ups can sometimes come across as rather dull. Some people used to complain about Mandela’s speeches; for example, a woman told Mandela that his first big speech at a rally after his prison release was “very boring." Mandela laughed at this accusation, because it didn’t bother him. He had learned after many years that providing clear, rational explanations is always better than being an excitable rabble-rouser.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #3: No matter what, stick to your core principles – everything else can be negotiated.

Few people realize what a pragmatist Mandela was. He would always re-think and re-work his strategies according to changing conditions.

But not all principles are equal. It is important to decide which are indispensable and which are negotiable.

When Mandela was a young man he was not so good at this. For example, he walked out of his university in protest over a rather petty issue involving poor quality food on campus and a consequent student council election boycott. His defiance may have seemed noble to him, but it cost him a valuable opportunity (rare for black people at the time) to get a university education that would enhance his ability to struggle for the much more important issue of national injustice. Mandela realized later, with good humour, that he had been a headstrong young man.

Once Mandela had established racial equality as his core principle, he was willing to negotiate the rest.

For example, the principle of nonviolence, which, for Gandhi, could not be compromised (any victory involving violence would be worthless), was simply a strategy to Mandela. When it proved ineffective in bringing down the brutal apartheid regime, he abandoned it. It was not his core principle.

Core principles provide goals. It is important to be realistic about how you plan to achieve them, and not to get caught up in abstractions. Mandela emerged from prison with the aim of finally ushering in a democratic and racially equal society, and he did not get too distracted by abstract models like socialism, capitalism or tribalism. He stuck to the practicalities of implementing a key social change – equal rights and opportunities for all.

So long as we stick to our core principles, we can adjust our contingent principles according to changing conditions – that is just being pragmatic.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #4: Nothing in life is black and white – accept life’s contradictions.

Being a complex, multifaceted man, Mandela harbored various contradictions and he was OK with that.

We too should realize that inconsistency is not a flaw: all of us are complex and it is natural that we have a variety of sometimes contradictory motives. Once, when asked about his motives for leading the anti-apartheid armed struggle – was it because nonviolence wasn’t working, or was it to prevent the ANC from falling apart? – Mandela answered, “Why not both?” As he saw it, most actions arise from multiple motives and not all are clear.

It is usually the rigidity of ideology that makes us see things in black and white. Mandela always carefully considered both sides of a dichotomy, such as tradition versus modernity, socialism versus free market capitalism, Afrikaners’ love of rugby versus black Africans’ hatred of it. It was because he respectfully considered all positions that he was so good at reconciliation.

It is not always possible, however, to make everybody happy. Although Mandela was willing to empathize with all positions in a debate, he sometimes had to favor those that were backed by the most convincing evidence.

For example, although AIDS was a tricky cultural issue in South Africa, Mandela knew that it was essential to follow the biomedical scientific advice on supplying retroviral drugs to the nation because it was backed by the best evidence.

While we may have core principles that we strongly believe to be valid, such as racial equality and universal democracy, for most issues we should see the many shades of gray in between the black and the white extremes.

This will encourage sympathy with many perspectives, an ability to compromise and a sensitivity that brings us close to what is usually called “wisdom.”

In the next book summary you will find out the key leadership skills that allowed Nelson Mandela to inspire others.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #5: Lead from the front: take the initiative, take risks and make sure you’re seen to be leading.

Mandela was always willing to take risks. One of the reasons he did this was because he wanted people to see that, as their leader, he would take risks on their behalf.

Mandela knew that leadership is often a display, and by showing people his capacity to lead he won trust, admiration and loyalty from his supporters.

For example, Mandela displayed fortitude and hope from the day he arrived at Robben Island prison where he and fellow political prisoners had been condemned to spend many years behind bars for challenging the apartheid system. As one prisoner explained, simply watching the way Mandela walked around in a confident manner, stable and unbroken by prison life, was extremely uplifting to the inmates.

In addition to displaying your willingness to lead from the front, you need to take initiative and make hard decisions. Mandela took the initiative to turn the once peaceful anti-apartheid movement into an armed struggle.

But the riskiest decision he ever made was a secret one – to begin negotiations with the apartheid government in 1985, against the will of his own party. After extensive consideration of the pros and cons, Mandela decided that negotiation would be the only effective course of action, even if his party might consider him a traitor when they found out. He therefore seized an opportunity to begin secret meetings.

This risky yet carefully considered decision-making is a great example of leading from the front.

But leadership does not mean entitlement to special treatment. Leaders must also show humility, a willingness to stoop down to hard tasks instead of just delegating them to others. One of the Robben Island prisoners recounted an episode where he was seriously ill and unable to clean out his own chamber pot. Despite being a leader of the prison’s biggest organization, Mandela took it upon himself to clean this man’s chamber pot for him.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #6: Great leaders don’t just lead from the front; they also guide from the back.

Being up front and spearheading a movement certainly allows you to enjoy the limelight. But the limelight also has to be shared. Sometimes leaders have to move to the rear and empower others to lead.

Leading from the rear was something Mandela learned from the age of eight, as a cattle herder. He used to put some of the cleverer cattle up at the front of the herd, and then steer from the back, using a stick. Although the herd would follow the leading cattle, it was in fact the boy at the back who was guiding them all. Mandela saw this as a metaphor for how to lead people.

Whether leading from the front or the back, being in command does not mean dictating; it must involve truly listening to others and working toward consensus.

For example, a Xhosa king, Jongintaba, who lived in the Transkei region, was a great inspiration to the boy who would become South Africa’s first black president. The king saw his leadership as a privilege, not as a right, and he always allowed others to voice their opinions. Decades later, Mandela ran his cabinet meetings in a similar way, always allowing others to speak before he did.

This style of leadership is based on the notion that group wisdom is greater than individual wisdom. This reflects the concept of Ubuntu, which suggests that people are empowered by other people. We must foster a spirit of collective action and collective decision-making, whether we are leading from the front or guiding other leaders from the back.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #7: Appearances matter: leadership is about looking the part.

Mandela was always concerned with his appearance – he wore clothes that suited his role, like battle fatigues when he became a military leader, smart suits when he was a lawyer, and eventually colorful shirts when he’d been president for a while, to show that African clothing was as dignified as Western clothing. He knew how important it is to “look the part."

What he realized is that everyone judges a book by its cover – appearances do matter. Therefore making a good first impression is important.

For example, when Mandela was still a prisoner in the 1980s, he arranged to meet the intimidating president of apartheid South Africa, P. W. Botha, for secret negotiations. Aware of the importance of the first impression, he insisted on acquiring a tailor-made three-piece suit before the meeting, so that he would not be put at a disadvantage just because of his “inferior” prison clothing. He also walked confidently across the room to shake Botha’s hand, which was not what the apartheid president expected of a black political prisoner.

Symbolism is just as powerful as substance, and great leaders know how to unite the two. One of the ways in which Mandela did this was by carefully planning how his policies would appear to the public and how symbolism could enhance their effectiveness. Even his radiant smile was highly effective – it was arguably one of the most important elements of his election campaign in 1994, because it communicated his desire for the nation to forgive and move on.

Appearances are not deceptions; they present ideals that eventually become reality. Mandela would decide who he ideally wanted to be and would then put on the appearance of such a person, until, eventually, he internalized those ideals and became that person. But this also took immense discipline; he had to hide the faults and emotions that would prevent him from looking and becoming a great leader.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #8: Because life is a long game, always take a long-term perspective.

Most of us tend to be impatient. Some even mistake impulsive behavior for “quick thinking” and being proactive. Mandela, similarly, was impatient as a young man. He wanted things to change immediately.

But 27 years in prison taught him to slow down, and to realize that, since racism, colonialism and apartheid had formed over a long period of time, it would take many years to dismantle them.

Our culture often rewards impatience – it is mistakenly taken to mean quick-thinking, boldness and decisiveness. But good decisions are not based on speed, they are based on direction. Accurately calculating the direction your decision will take further down the line requires a long-sighted perspective, not impatience and impulsiveness.

In prison, Mandela’s fellow inmates often hassled him for not making quick decisions. But he always answered that it was important to think about how everything will pan out in the long run. With such long-horizon estimations, he made wise decisions that ultimately proved successful in transforming South Africa’s political situation.

It is history that makes the man and not man who makes history. Mandela saw himself simply as a key actor in a significant historic moment – he had to work out how to optimize the opportunities history had given him, so that future generations would judge him favorably. In the end, history judged him favorably because most of his estimations turned out to be accurate.

Because life is a long game, it is unfair to judge people by single acts they have committed. No one can be considered as great as their noblest actions, or as evil as their most depraved ones. We are the sum of all our actions. Although Mandela was disappointed by the weakness of some of his prison comrades in standing up for certain issues, he never judged them on that basis alone; he always claimed that they had honor and integrity overall.

In the following book summary you will discover which people skills made Nelson Mandela so popular with people from all walks of life.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #9: Always seeing the good in others is not naive; it is the best way to bring out their good side.

Despite decades of hardship and ill treatment in apartheid South Africa, Mandela was extraordinarily positive in his assessment of most people – even some of those who had oppressed him.

This was because he knew that no one should be judged entirely by their behavior – social pressure and ignorance can make people do terrible things, but this does not make them purely evil. He therefore rarely spoke ill of someone and preferred to see the good.

A great example of this is his fond remembrance of how polite the Nazi-sympathizing president of South Africa, John Vorster, had been, even though he had wanted Mandela executed! Instead of dwelling on the bad side, Mandela remembered Vorster as “a decent chap."

Seeing the good in others is not naive; it actually tends to bring out their good side. Mandela was often successful at encouraging ignorant or unsympathetic people to discover their own humanity.

A great example was his encounters with a racist priest on Robben Island. Although the priest preached the divinely ordained separation of races and despised the prisoners’ politics of racial equality, he was not intrinsically an evil man. Mandela saw that it was an ignorant and insecure society that had taught the priest to think that way.

Therefore, rather than hate him, Mandela chose to look past the abusive language and engage in sincere discussion, eventually managing to persuade the priest that the struggle for racial justice was a noble one.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #10: Life brings you into many confrontations, so get to know your opponents well.

Mandela learned from his boxing coach in the 1950s that beating the opponent was not just about being fit and throwing good punches. It was also about knowing your opponent – his habitual movements and reactions during a fight.

In a similar way, this insight applies in the political arena. For most of his life, Mandela’s biggest “enemy” were the Afrikaners who maintained apartheid.

In his struggle against white domination, Mandela became leader of the anti-apartheid ANC’s military wing and went underground. During this period, he not only read books like The Art of War, but also learned Afrikaans grammar and poetry. Why?

Because he was looking ahead to the day when he would inevitably need to negotiate with “the enemy," and knew that mastering their language was the best way to go straight to their hearts.

Speaking to the heart of your enemy isn’t just a tactic; it reflects genuine empathy for them.

Mandela’s empathy for Afrikaners grew when he realized that they had a lot in common with black South Africans – South Africa was their only home, and, like blacks, they had been oppressed by the British; deep down lay a lingering insecurity.

By learning a lot about their proud military history and the iconic Afrikaner sport – rugby – Mandela was able to bridge the cultural gap. In fact, an army major who had been extremely hostile to black freedom fighters found himself eventually engaging warmly with Mandela, simply because the latter had taken the time to learn all about the latest rugby news.

Being empathetic can win your opponent over to your side; but this makes them feel vulnerable. It is therefore not a time to celebrate or gloat. Even though it was a great achievement for Mandela to win the trust and appreciation of many Afrikaners through his efforts to reach out to them, he was very careful not to humiliate them. Instead, he let the Afrikaners save face.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #11: Keep a close eye on your “friendly rivals” – you never know whether they’re with you or against you.

In some ways friends and enemies are equally reliable – the first are always with you, the second are always against you. But friendly rivals are somewhere in between. More than anyone else, they’re the ones you should keep close by you so that you can anticipate their next move.

Don’t just prepare for the unexpected; prepare for the expected. You can always expect your rivals to challenge you – be prepared for it.

Mandela was particularly keen to know what his friendly rivals thought and felt.

For example, he distrusted a fellow leader in the anti-apartheid struggle who was a Zulu and who headed another political party. Precisely because this man seemed dangerous and sly, Mandela made him a member of his cabinet, where he could watch him closely. He similarly keenly observed other cabinet members, knowing that if any of them didn’t look him in the eye, there was something wrong.

Mandela was not so naive as to expect total loyalty from anybody; he knew that loyalty is often self-interested.

By keeping your rivals close you can sometimes bring them under your wing.

This was what Mandela managed with the young militant leader of the ANC, Bantu Holomisa, who was thirsty for vengeance rather than willing to seek reconciliation with whites, which was Mandela’s approach. Before long, however, Holomisa felt flattered by Mandela’s compliments, and he was always trying to please the leader. Thus a potentially dangerous rival became a more trustworthy compatriot.

Mandela’s Way Key Idea #12: Saying no can be very difficult, but if it has to be done, say it clearly and firmly.

Mandela liked to please people as much as possible. He made sure everyone experienced “the whole Mandela”: the radiant smile, the courtesy, the openness to all sides of an argument. But what he did not do was deceive people just to please them. This means that he knew when he had to say no, even if saying it would disappoint others.

Many of us are insecure and apologetic when we try to say no. This insecurity can easily be used against us. It is therefore essential to be clear and firm – not ambivalent – when we feel that no is the only right answer.

Showing insecurity would not have worked for Mandela at the times in his political career when he had to say some very big nos. One such occasion was toward the end of the apartheid era, when the president of South Africa, F. W. De Klerk, was trying to maintain white dominance during the negotiations. Mandela was willing to compromise on less significant issues, but when his core principle of racial equality was undermined, he knew he had to put his foot down and say “no!”

But Mandela never liked to be direct when he didn’t have to be; he seemed to realize that it’s worth saving up one’s emphatic nos for when one really has to use them.

A typical example of this was his reply to a question about whether he had enjoyed a trip to the mountains: “I didn’t hate them," he said. Many South Africans loved those mountains; so what was the point of giving a negative response?

If you don’t have a choice – if you know you must say no – it is much better to do it sooner rather than later. Facing it now will save you a lot of trouble down the line. However, if you realize that you don’t need to be so firm or confrontational, then why not save your no for when it’s really needed?

Final summary

Final summary

These book summary show us how the self-discipline, strength of character, courage, vision and democratic spirit embodied in South Africa’s great liberation leader, Nelson Mandela, are values and virtues that all of us can develop through hard work, patience, and commitment. He is an example to us all, showing that it is possible to stay true to our core principles and achieve great things under even the most trying circumstances. Luckily, most of us will never face the threat of execution, the brutality, the fear for our families’ safety and the 27 years in prison that Mandela had to cope with before he could reach his goals.